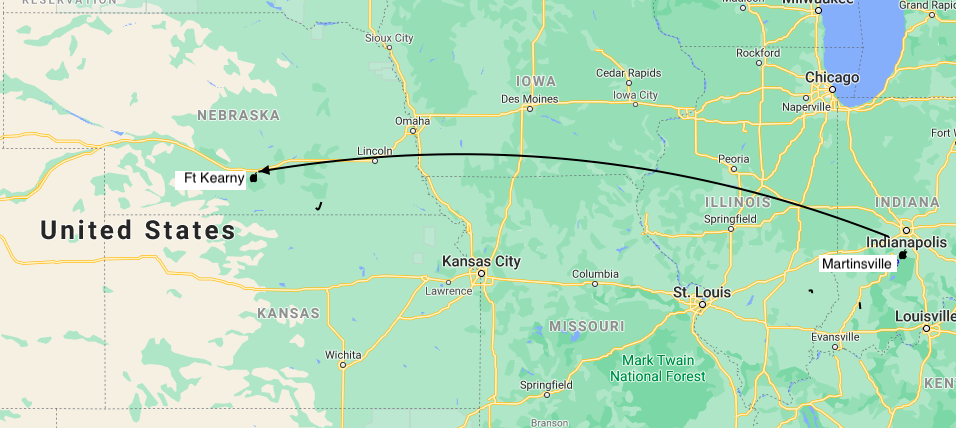

The distance covered by Margaret and Ledyard Frink from Martinsville, Indiana to Fort Kearny, was just under 800 miles.

The distance covered by Margaret and Ledyard Frink from Martinsville, Indiana to Fort Kearny, was just under 800 miles. Roger M. McCoy

Margaret Frink, aged thirty-two, set off for California in 1850 from Martinsville, Indiana, with her husband Ledyard Frink and a twelve-year-old neighbor boy. In the next two blogs I hope to cover the essence of Margaret Frink’s twenty-three weeks on the trail to Sacramento.

Everyone was eager to get to California before the gold was all gone. As they neared Fort Kearny, in present day Nebraska, where two branches of the trail converged, Margaret Frink wrote. ”I thought, in my excitement, that if one-tenth of these people got ahead of us there would be nothing left in California worth picking up.”

Gold vs. Grass

The vast number of people and animals presented a major problem with the availability of grass along the way. Those who started earliest got the grass first. In addition to grazing the animals as they progressed, the early travelers also harvested grass and made hay to carry with them in the wagons to help them through barren areas. Getting to the gold first was a desire for wealth, but getting the grass first was a matter of survival. If animals died in the arid land of Nevada, the people must abandon most of their possessions and continue on foot, perhaps with a makeshift two-wheel cart improvised from their wagon.

One witness to this massive migration, Major Osborne Cross, wrote that in the few weeks between late April and June 1st of 1849 four thousand wagons carrying approximately 16,000 people passed Fort Kearny. Major Cross noted that this number included only those traveling along the south bank of the Platte River, and that there were also substantial numbers traveling along the north bank. One historian studied the migrations and concluded that approximately 500,000 people traveled along the Platte River during the years from 1841 to 1866 heading for Oregon, California, and Utah. This means that about 2 percent of the American population at that time became migrants. More than two thousand of those migrants kept diaries or later wrote memoirs of their trip experience.

My friend Michael Yeager compares the eager anticipation for some people when moving to a new place versus the anxiety for others of change and leaving home and friends. He uses the term “nomads” for those who feel comfortable with, or even welcome, a change of location. Many of the migrants certainly were nomads and America soon became a nation of nomads.

Risks vs. Rewards

Most migrants were optimists concerning the opportunities ahead in California, but there were instances of strong pessimism and anxiety. A Mrs. Simpson was so apprehensive about the journey that she made burial shrouds for each member of her family before beginning her journey. A few families carried precut boards for coffins that could be assembled as needed. Everyone recognized the dangers but believed that the likelihood of success was worth the risk. The dangers were well known. Diarists mention accidental gunshot wounds from hunting or while placing a rifle in the wagon. Children sometimes walked too close to a wagon wheel and were run over. Drownings sometimes occurred during river crossings. Poisoning from bad food, toxic plants, or cholera from contaminated water could be fatal. One effect the journey had on many travelers was a feeling of sadness or depression due to leaving their home and friends behind. Despite all these horrors most migrants reached their destination safely.

One of the travelers’ greatest anxieties was attacks by the native tribes of the Great Plains. These fears were fueled by publicized paintings, dime novels, and newspaper stories. Although serious incidents occurred, usually involving attempted horse-theft at night, most contacts with Native Americans were peaceful and typically involved trading food for manufactured items like knives, rope, or various other items. Meanwhile back to the experience of Margaret Frink from Indiana.

The Frinks Go For the Gold

Margaret Frink kept such an extensive diary that her husband had it printed as a book after her death in 1893 with this ponderous title:

“JOURNAL of the Adventures of a Party of California Gold-Seekers

Under the guidance of MR. LEDYARD FRINK During a journey

across the plains from Martinsville, Indiana to Sacramento,

California from March 30, 1850 to September 7, 1850. From the

Original Diary of the trip kept by MRS. MARGARET A. FRINK.”

Margaret and her husband Ledyard, whom she always called “Mr. Frink,” watched in Indiana while neighbors and family members headed for California. The letters sent from her friends in California told glowingly about “the delightful climate” (tempting—she was in Indiana you know) and the “abundance of gold.” This news was enough to give Mr. and Mrs. Frink a case of California fever. They had a successful farm, many friends and family ties, and they had no awareness of the difficulties faced by those who traveled to the gold fields, but they wanted to go. Neighbors tried to dissuade them, but the Frinks sold the farm and left it all behind the following spring (1850). They had no children, but a neighbor’s twelve-year-old son wanted to go with them and his parents agreed.

Mr Frink heard from letters that lumber cost $400 per thousand board feet in California. Because he could buy it in Indiana for $4 per thousand, he decided to buy in Indiana all the lumber needed for a California house. He bought a house plan and hired carpenters to cut all the lumber to dimensions specified by the plan, and sent the ready-to-assemble house by ship to San Francisco. (Remember he had a lot of cash from selling the farm.) His pre-cut lumber went by boat down the Wabash River to the Ohio, then to the Mississippi, all the way to New Orleans where it was loaded on a ship headed around Cape Horn to San Francisco. Travel time by water from Indiana and around the Horn to San Francisco in 1850 was at least one hundred days, plus time for transferring the load from a river boat to a sailing ship.

The Frinks bought a new wagon with storage spaces designed especially for the long trip. They had a rubber air-mattress and a feather bed with feather pillows. The inside of the wagon was lined with green cloth to make it “pleasant and soft to the eye.” The green lining also had four large pouches on each side to hold various personal items—“looking-glasses, combs, brushes, and so on.” Her prized possession was a “small sheet-iron cooking stove, which was lashed on behind the wagon.” They carried “plenty of hams and bacon, apples, peaches, rice, coffee, beans, flour, corn-meal, crackers, sea-biscuit (hardtack), butter, and lard. Mrs. Frink’s diary covers every day of her trip in well-written detail.

In the middle of May, and about six weeks from home, the Frinks finally crossed the Missouri River by ferry. They crossed into Nebraska just below the mouth of the Platte River, about ten miles south of present day Omaha. At this point they began to meet other people traveling to California and Margaret observed that the “wide expanse of the great plains is before us, we feel like mere specks on the face of the earth.” This was their first day out of the United States as Nebraska was not yet a territory.

At this point the Frinks began to realize the magnitude and perils of the country ahead of them. Printed leaflets warned of dangers from native tribes ahead and Margaret Frink commented on their defenseless situation having only one rifle and one pistol. She wrote that they became aware of the importance of joining with other groups headed west. Many people told her there was nothing to fear, but she had become very uneasy.

After traveling through the first day her group spotted several native horsemen on a nearby hilltop. They immediately circled the wagons to form a corral and prepared their camp for defense against attack. Margaret was in a high state of anxiety and awake, fully dressed, all night to make sure the guards stayed awake. Meanwhile she felt bothered that Mr. Frink could be sleeping so soundly, and she roused him occasionally. Like most cases of worry nothing actually happened. The next morning their small group encountered a large wagon train and joined them for the remainder of the trip.

As they progressed westward along the Platte River, Mrs. Frink wrote that the country was “so level that we could see long trains of white-topped wagons for many miles. It seemed to me that I had never seen so many human beings in all my life.” Fearing there would be nothing left for them in California Margaret Frink urged greater speed in their travel, but her husband argued that moving faster would exhaust the horses and they would never arrive in California. Margaret fretted that every blade of grass would be eaten by the thousands of mules, horses, and oxen ahead of them. But “worse than all,” she wrote, “there would be only a few barrels of gold left for us when we got to California.” Margaret had the notion from friends’ letters that some people actually found gold by the barrel. By this time about seven weeks and over 700 miles had passed since they left the farm in Indiana. They had reached Fort Kearny in the middle of present-day Nebraska, and they still had many miles to go.

To Be Continued

Sources

California Trail. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_Trail.

Holmes, Kenneth L. Best of Covered Wagon Women. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.

Margaret Frink, aged thirty-two, set off for California in 1850 from Martinsville, Indiana, with her husband Ledyard Frink and a twelve-year-old neighbor boy. In the next two blogs I hope to cover the essence of Margaret Frink’s twenty-three weeks on the trail to Sacramento.

Everyone was eager to get to California before the gold was all gone. As they neared Fort Kearny, in present day Nebraska, where two branches of the trail converged, Margaret Frink wrote. ”I thought, in my excitement, that if one-tenth of these people got ahead of us there would be nothing left in California worth picking up.”

Gold vs. Grass

The vast number of people and animals presented a major problem with the availability of grass along the way. Those who started earliest got the grass first. In addition to grazing the animals as they progressed, the early travelers also harvested grass and made hay to carry with them in the wagons to help them through barren areas. Getting to the gold first was a desire for wealth, but getting the grass first was a matter of survival. If animals died in the arid land of Nevada, the people must abandon most of their possessions and continue on foot, perhaps with a makeshift two-wheel cart improvised from their wagon.

One witness to this massive migration, Major Osborne Cross, wrote that in the few weeks between late April and June 1st of 1849 four thousand wagons carrying approximately 16,000 people passed Fort Kearny. Major Cross noted that this number included only those traveling along the south bank of the Platte River, and that there were also substantial numbers traveling along the north bank. One historian studied the migrations and concluded that approximately 500,000 people traveled along the Platte River during the years from 1841 to 1866 heading for Oregon, California, and Utah. This means that about 2 percent of the American population at that time became migrants. More than two thousand of those migrants kept diaries or later wrote memoirs of their trip experience.

My friend Michael Yeager compares the eager anticipation for some people when moving to a new place versus the anxiety for others of change and leaving home and friends. He uses the term “nomads” for those who feel comfortable with, or even welcome, a change of location. Many of the migrants certainly were nomads and America soon became a nation of nomads.

Risks vs. Rewards

Most migrants were optimists concerning the opportunities ahead in California, but there were instances of strong pessimism and anxiety. A Mrs. Simpson was so apprehensive about the journey that she made burial shrouds for each member of her family before beginning her journey. A few families carried precut boards for coffins that could be assembled as needed. Everyone recognized the dangers but believed that the likelihood of success was worth the risk. The dangers were well known. Diarists mention accidental gunshot wounds from hunting or while placing a rifle in the wagon. Children sometimes walked too close to a wagon wheel and were run over. Drownings sometimes occurred during river crossings. Poisoning from bad food, toxic plants, or cholera from contaminated water could be fatal. One effect the journey had on many travelers was a feeling of sadness or depression due to leaving their home and friends behind. Despite all these horrors most migrants reached their destination safely.

One of the travelers’ greatest anxieties was attacks by the native tribes of the Great Plains. These fears were fueled by publicized paintings, dime novels, and newspaper stories. Although serious incidents occurred, usually involving attempted horse-theft at night, most contacts with Native Americans were peaceful and typically involved trading food for manufactured items like knives, rope, or various other items. Meanwhile back to the experience of Margaret Frink from Indiana.

The Frinks Go For the Gold

Margaret Frink kept such an extensive diary that her husband had it printed as a book after her death in 1893 with this ponderous title:

“JOURNAL of the Adventures of a Party of California Gold-Seekers

Under the guidance of MR. LEDYARD FRINK During a journey

across the plains from Martinsville, Indiana to Sacramento,

California from March 30, 1850 to September 7, 1850. From the

Original Diary of the trip kept by MRS. MARGARET A. FRINK.”

Margaret and her husband Ledyard, whom she always called “Mr. Frink,” watched in Indiana while neighbors and family members headed for California. The letters sent from her friends in California told glowingly about “the delightful climate” (tempting—she was in Indiana you know) and the “abundance of gold.” This news was enough to give Mr. and Mrs. Frink a case of California fever. They had a successful farm, many friends and family ties, and they had no awareness of the difficulties faced by those who traveled to the gold fields, but they wanted to go. Neighbors tried to dissuade them, but the Frinks sold the farm and left it all behind the following spring (1850). They had no children, but a neighbor’s twelve-year-old son wanted to go with them and his parents agreed.

Mr Frink heard from letters that lumber cost $400 per thousand board feet in California. Because he could buy it in Indiana for $4 per thousand, he decided to buy in Indiana all the lumber needed for a California house. He bought a house plan and hired carpenters to cut all the lumber to dimensions specified by the plan, and sent the ready-to-assemble house by ship to San Francisco. (Remember he had a lot of cash from selling the farm.) His pre-cut lumber went by boat down the Wabash River to the Ohio, then to the Mississippi, all the way to New Orleans where it was loaded on a ship headed around Cape Horn to San Francisco. Travel time by water from Indiana and around the Horn to San Francisco in 1850 was at least one hundred days, plus time for transferring the load from a river boat to a sailing ship.

The Frinks bought a new wagon with storage spaces designed especially for the long trip. They had a rubber air-mattress and a feather bed with feather pillows. The inside of the wagon was lined with green cloth to make it “pleasant and soft to the eye.” The green lining also had four large pouches on each side to hold various personal items—“looking-glasses, combs, brushes, and so on.” Her prized possession was a “small sheet-iron cooking stove, which was lashed on behind the wagon.” They carried “plenty of hams and bacon, apples, peaches, rice, coffee, beans, flour, corn-meal, crackers, sea-biscuit (hardtack), butter, and lard. Mrs. Frink’s diary covers every day of her trip in well-written detail.

In the middle of May, and about six weeks from home, the Frinks finally crossed the Missouri River by ferry. They crossed into Nebraska just below the mouth of the Platte River, about ten miles south of present day Omaha. At this point they began to meet other people traveling to California and Margaret observed that the “wide expanse of the great plains is before us, we feel like mere specks on the face of the earth.” This was their first day out of the United States as Nebraska was not yet a territory.

At this point the Frinks began to realize the magnitude and perils of the country ahead of them. Printed leaflets warned of dangers from native tribes ahead and Margaret Frink commented on their defenseless situation having only one rifle and one pistol. She wrote that they became aware of the importance of joining with other groups headed west. Many people told her there was nothing to fear, but she had become very uneasy.

After traveling through the first day her group spotted several native horsemen on a nearby hilltop. They immediately circled the wagons to form a corral and prepared their camp for defense against attack. Margaret was in a high state of anxiety and awake, fully dressed, all night to make sure the guards stayed awake. Meanwhile she felt bothered that Mr. Frink could be sleeping so soundly, and she roused him occasionally. Like most cases of worry nothing actually happened. The next morning their small group encountered a large wagon train and joined them for the remainder of the trip.

As they progressed westward along the Platte River, Mrs. Frink wrote that the country was “so level that we could see long trains of white-topped wagons for many miles. It seemed to me that I had never seen so many human beings in all my life.” Fearing there would be nothing left for them in California Margaret Frink urged greater speed in their travel, but her husband argued that moving faster would exhaust the horses and they would never arrive in California. Margaret fretted that every blade of grass would be eaten by the thousands of mules, horses, and oxen ahead of them. But “worse than all,” she wrote, “there would be only a few barrels of gold left for us when we got to California.” Margaret had the notion from friends’ letters that some people actually found gold by the barrel. By this time about seven weeks and over 700 miles had passed since they left the farm in Indiana. They had reached Fort Kearny in the middle of present-day Nebraska, and they still had many miles to go.

To Be Continued

Sources

California Trail. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_Trail.

Holmes, Kenneth L. Best of Covered Wagon Women. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed