Site of Quintina Snodderly’s grave near the North Platte River east of Casper, Wyo. The fence and marker were erected by the Oregon-California Trails Association. Randy Brown photographer.

Site of Quintina Snodderly’s grave near the North Platte River east of Casper, Wyo. The fence and marker were erected by the Oregon-California Trails Association. Randy Brown photographer.

Life on the westward trails was very difficult even in the best of conditions. Weather was an adversary with extremes of heat or torrential rains and flooded streams. Along with environmental hazards there was the ever present danger of life-threatening illness, especially cholera, typhoid, or dysentery.

Wagon trains usually had no trained doctor and most treatments for diseases consisted of home remedies and a prayer, neither of which gave a reliable outcome. Most people in the nineteenth century had some knowledge of remedies for various diseases and books provided a complete list. One such book of home remedies included the two recipes below:

A recipe for “Cough Surrup” was: Boil the lickrish root to thick molasses. Take 1 fluid oz Balm Gilead buds, 1 gil vinigar, 1 gil strong sirrip of skunk cabbage root, ½ fluid oz tincter libelia. Take a tea spoon full or so as often as the case requires to keep the plegm loos to rais easy.

Another called “Mother’s Relief” was a mixture of herbal extracts: including partridge berry vine, unicorn root, blue cohusk, spikenard, bayberry bark, birthroot, raspberry leaves, witch hazel leaves and lady slippers. This was recommended for women to ease the labor of childbirth.

At least one expectant mother had neither time nor need for making childbirth medicines. Mary Richardson Walker wrote a diary entry on the day of her birth labors:

March 16, 1842: Rose about five. Had early breakfast. Got my work done about 9. Baked six loaves of breads, made a kettle of mush and have now a suet pudding and beef boiling. I have managed to put my clothes away and set everything in order. May the Merciful be with me through the unexpected scene. Nine o’clock p.m. was delivered of another son. [Her statement about the “unexpected scene” was probably a prayer that nothing unexpected would arise.]

Other remedies carried by most migrants in the mid-nineteenth century:

Essence of peppermint for stomach aches.

Pine tar and turpentine for coughing, sore throat, and croup.

Laudanum is an alcoholic solution containing morphine made from opium and used as a

narcotic painkiller. It eased pain and many thought it would also treat cholera, but it was

of no help with diseases.

Whiskey was considered a cure-all, but had little real benefit except for the “feel-good

factor.” It may have helped some with pain.

Hartshorn was made from red deer antlers and was used successfully for insect bites and unsuccessfully for snake bites.

Quinine tea was a treatment for malaria.

Chamomile tea was used for stomach problems and muscle aches. It is still used as a

refreshing drink today.

Vinegar was taken for cholera, but was ineffective.

Castor oil or “Physicking” pills used as a laxatives.

Hazards of Travel

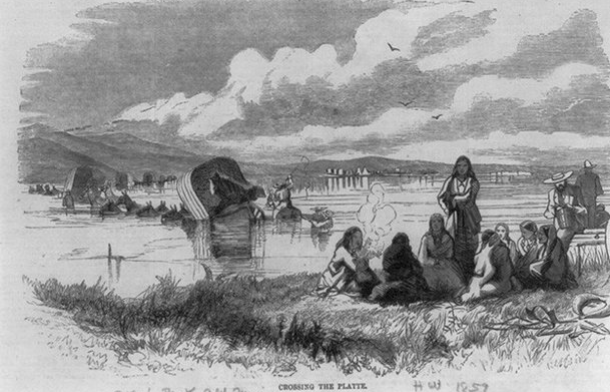

Migrants encountered many natural hazards on the westward trails. Weather hazards included thunderstorms with high winds, dangerously large hailstones, lightning, and tornadoes. Intense summer heat on the Great Plains caused wood to dry and shrink, and sometimes wagon wheels had to be soaked in rivers at night to keep their iron rims from falling off during the day. The dust on the trail itself could be two or three inches deep and as fine as flour. After a heavy rainstorm the dust turned to mud and slowed movement. Ox shoes sometimes fell off and hooves split. The emigrants’ lips blistered and split in the dry air, and their only remedy was to rub axle grease on their lips. River crossings were probably the greatest danger.

Add to these hazards the high potential for accidents. Accidents were caused by negligence, exhaustion, guns, animals, and the weather. Every wagon carried at least one gun and the owner sometimes inadvertently shot himself, a friend, or perhaps one of the draft animals when a gun discharged accidentally. Drownings, being crushed by wagon wheels, and injuries from handling domestic animals also led to accidental deaths on the trails.

Almost ten percent of the migrants on the western trails did not survive the trip. The primary cause of death was disease followed closely by accidents. Cholera was the worst of the illnesses, but dysentery and typhoid were close behind. All three ailments were carried by contaminated water in streams and poor sanitation. Cholera was especially fast acting. A person could feel normal in the morning, in agony by noon and dead by evening. If death did not occur within the first twelve to twenty-four hours, the victim usually recovered. Children and the elderly were most vulnerable to any of these diseases. Martha Freel wrote of losing most of her family in the summer of 1852, …”we have lost 7 persons in a few short days, all died of Cholera.”

Deaths along the trail, especially among young children and mothers in childbirth, were the most heart-rending of trail tragedies. The hazards of accidents and disease created a constant awareness of death and resulted in great sorrow and grief for many migrants. The numerous graves dotting the prairies were the evidence of these tragedies. Over a twenty-five year span approximately 65,000 deaths occurred along the western overland emigrant trails, an average of 2,600 per year.

Accidental death was as almost as great a hazard as illness. One traveler wrote about witnessing a child’s accidental death, “Mr. Harvey’s young little boy Richard 8 years old went to git in the waggon and fel from the tung. The wheals run over him and mashed his head and Kil him Ston dead he never moved.”

River crossings were probably the most dangerous thing pioneers did. Swollen rivers could upset wagons and drown people and oxen. Such accidents could cause the loss of life and most or all of valuable supplies. Animals could panic when wading through deep, swift water, causing wagons to overturn. Even if the current was slow and the water shallow, wagon wheels could be damaged by unseen rocks or become mired in the muddy bottom. Enterprising men ran ferries at large river crossings and charged a fee for carrying wagons

and teams to the other side.

Disease and Death on the Trail.

The most common deadly diseases on the western trails were caused by poor sanitation and contaminated water. Along the trails there were few opportunities for bathing and laundering, and safe drinking water frequently was not available in sufficient quantities. Human and animal waste, garbage, and animal carcasses were often discarded in close proximity to available water supplies. If these waste materials were contaminated with typhoid, cholera, or dysentery bacteria, those diseases could be transmitted to every wagon train that came along.

In 1852 Lydia Rudd wrote, “We have not moved today. Our sick ones not able to go. The sickness on the road is alarming – most all prove fatal.” A Mr. Page wrote, “You were OK in the morning, but dead by noon. There really wasn’t much you could do for cholera.”

Trail deaths meant heartbreak and hardship for survivors, but little time was allowed for grieving. A grave was hurriedly prepared beside the trail and a prayer offered. Someone might volunteer to read a passage from the Bible, or "say a few words," after which the journey continued. Occasionally the dead were simply abandoned beside the trail, or the grave was dug in the trail itself to help conceal it. Death due to contagious disease meant increased haste to complete the journey before more calamity hit.

Graves were usually shallow to save labor, and often located in a natural depression. As much soil was scooped out as possible, and earth and rocks were mounded over the remains. Sorrowing relatives sometimes transplanted prairie sod and wild flowers, and set up some type of wooden marker, probably with the thought of returning some day to provide a more permanent memorial. Few did, however, and only a small percentage took time to erect a headstone. Many migrants graves are still preserved today, thanks to local and state historical societies.

Sources

Bagley, Will. With Golden Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West

1849-1852. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2012.

Bromberg, Erik. Frontier Humor: Plain and Fancy. Oregon Historical Quarterly,

September 1960

Werner, Morris W. Emigrant Graves on the Oregon and California Trails in

Kansas. (no date). http://www.kansasheritage.org/werner/emigrave.html

Larsell, O. The Doctor in Oregon. Portland: Binfords. 1947.

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/disease-death-overland-trails/2/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed