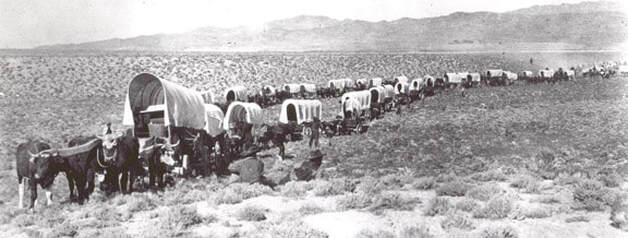

Wagon trains in 1855 traveling through a dry landscape with little grass for livestock.

Wagon trains in 1855 traveling through a dry landscape with little grass for livestock. Roger M McCoy

The California Trail,Part 1

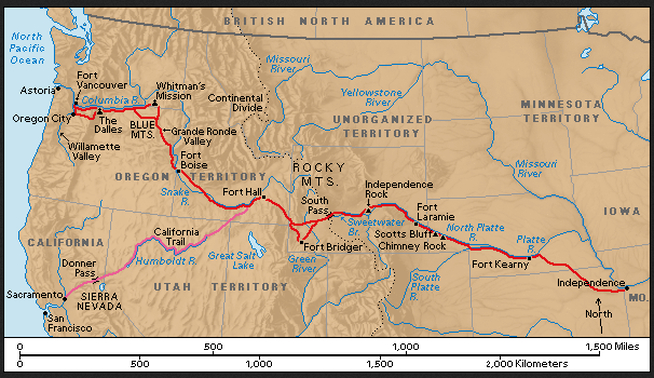

The California Trail turned away from the Oregon Trail about sixty miles east of present day Idaho Falls, and headed southwest toward the beginning of the Humboldt River near present day Wells, Nevada. The source of the Humboldt River main stem in northeastern Nevada is a spring called Humboldt Wells. From that point the wagon trains headed westward following the Humboldt River to its end in the Humboldt Sink. This article covers the California Trail emigrants along the Humboldt River.

About 300 diaries written by migrants on the California Trail provide a wealth of insight into travel through the harsh and unfamiliar terrain of the Great Basin Desert, mostly within the present State of Nevada. Weeks of travel along the Humboldt River through scorching heat and stifling dust taxed the endurance of men, women, horses, mules, and oxen. The saving factor that made such a trip possible was the Humboldt River itself. The river provided water for most of the route across the Basin, and supported grass of variable quality along its shores. The diaries of those nineteenth century migrants give accounts of distances, quality of water and grass, and the general conditions and hardships the travelers faced. The following is a sampling written during crossings from 1849 to 1855 through the Great Basin.

One migrant, James Wilkins, expressed his strong opinion of the Great Basin, “…the most detestable countries God ever made, to say nothing of its sterility and barrenness.” The wagon trace followed the river for almost 300 miles, but for most migrants the trip seemed unending, partly because they had no certain way of knowing how much farther they had to go.

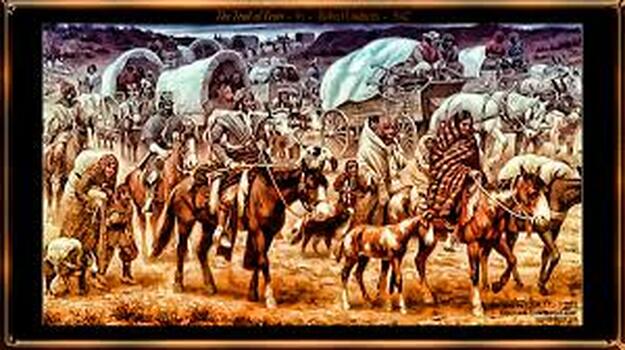

Often one wagon train was followed closely by others, sometimes creating a congestion of people. The route became so crowded at times that A.H. Houston wrote, “The immense crowd on the road made the trip more difficult and disagreeable. If you tried to pass other trains, you broke down your team in doing so. If you laid by to recruit, hundreds of teams were passing daily, making it more difficult to procure grass.” (The word “recruit” was commonly used in the nineteenth century meaning replenish or refresh.) Finding adequate grass for livestock was a daily problem. Some stretches of the trail offered good grass, but in many places grass was inadequate. Joseph Wood, lamenting the poor grass as his cattle began wasting away, wrote, “The grass does not contain sufficient nourishment for teams that have so much work to perform and hardships to endure.”

As they went downstream conditions grew worse daily. Charles Tinker: “Feed grew scarcer & water poorer & the weather hotter.” As the river water became more alkaline the travelers began to hate the river. Elisha Perkins wrote, “I must agree with the majority of the Emigrants in nicknaming it ‘Humbug River.” He added that the “river had become only a good sized creek. We could hardly get enough for our mules to eat and water barely drinkable from saline and sulfurous impregnation and having a milky color.”

Another constant problem was the six to ten inches of dust that lay on the trail raising choking clouds into the air. William Z. Walker wrote, “The dust along the stream in intolerable, filling our eyes so that we could hardly see our animals. We were visited by such a hurricane of dust during the forenoon that we were obliged to turn out of the road and stop till the wind subsided.” John Middleton added, “Our poor faded and exhausted cattle! It harrowed my soul that I could render them no relief—that we must rush on to save our lives at the expense of others. Poor obedient creatures, what hellish cruelties I have seen inflicted on them by hard-hearted men.” Unfortunately the travelers who arrived later in the summer found conditions worse because the grass had not sufficiently recovered from the passage of earlier wagon trains. Wagon wheels passing through the hot dust dried to the point that their wooden wheels rattled “like a bag of bones” as they turned. Not surprisingly many migrants had buyers remorse as conditions worsened. Joseph Wood wrote, “I would give One Dollar for a newspaper, Five for a letter and Fifty to see our friends. We shall be glad to leave the valley of the Humboldt.”

The marshy conditions at the terminus of the Humboldt River provided good stands of grass and the travelers stopped long enough to cut ample grass to carry for the perilous trek across the Carson Sink. Through August the grassy meadow was crowded with emigrants. Thomas van Dorn wrote, “Without this grass here, this route would be abandoned, but it forms a natural recruiting point in this vast desert region,”

Near today’s Lovelock, Nevada, the nearly depleted Humboldt River spread out into a vast playa and intermittent wetland called Humboldt Sink, now shown on maps as Humboldt Lake. This harsh dry lake bed, or playa, merged with another massive playa, the Carson Sink, formed at the terminus of the Carson River flowing from the Sierra Mountains. The two great playas were separated by a low, almost imperceptible, divide called the Humboldt Bar. The Carson Sink became known to migrants as “The Forty-mile Desert.” The scene on the Forty-mile Desert is bleak, flat, and featureless. The Carson Sink is visible as you speed by on Interstate 80 and one can only imagine crossing it on foot or in a slow-moving wagon.

Migrants often wrote of their disgust for conditions at the end of the Humboldt. Amasa Morgan lamented that, “This river that forces its way 290 miles through narrow Kanyans sandy deserts and around many a mountain here is lost in the earth, and whare its waters go to no one knows.” David Hindman called the area “a pool of black, stagnant water…upon which the stillness of death was resting.” A migrant named Addison Crane wrote a poem expressing his disdain for the Humboldt River:

Farewell to thee, thou stinking, turbid stream,

Amid who's waters frogs and serpents glean.

Thou putrid mass of filth, farewell forever.

At the Humboldt Bar the trail divided with one branch going northwest to the Truckee River and the other southeasterly to the Carson River. Both distances were about the same which most diaries estimate to be a little more than forty miles. Rumors and advice based on hearsay persuaded travelers that one or the other route would be better to take. Actually they were about equally bad. The Truckee route led to Donner Pass and the Carson route crossed the Sierra Nevada at Carson Pass. Crossing the Sierras is the subject of another blog. Before crossing the Forty-mile Desert, they first tried to prepare for their animals. They filled everything that could hold water—kegs, boilers, kettles, coffee pots, and rubber boots, and cut extra grass to carry over the desert expanse.

Joseph Berrien said the forty-five miles of desert had fifteen miles of heavy sand and advised, “Be careful to drive in the night. Expect to find the worst desert you ever saw and you will find it worse than you expected.” Thomas Evershed described his first impression of the Carson Sink as, “a beautiful sheet of water seemingly about a mile across with the reflections of the mountains in it. …it was a mirage, the first we had seen. Soon it disappeared, leaving not a trace behind except the carcass of an old ox. Oh! For a drink of good ice water.”

Whether traveling by day or night the Carson Sink was a perilous time for man and beast. One migrant wrote, “During the day our supply of water became exhausted. The teams began to fail. The roadside was almost covered with the carcasses of animals that could not make further progress and lay there.” When the animals died there was no way to pull the wagon, leaving many wagons abandoned along the roadside. They reported that the dead animals created “unsupportable stench, while the moans and creaky teeth of the yet living was enough to move a dragon to pity. Wagons abandoned by their owners are to be seen in every direction.”

Writing about the Forty-mile Desert crossing Luzena Wilson wrote, “It was a hard march over the desert. The men were tired of goading on the poor oxen which seemed ready to drop at every step. They were covered with a thick coating of dust, even the tongue which hung from their mouths was swollen with thirst and heat.” Wilson continued his description of the desert crossing and told of the change he saw as they neared the Carson River. “The miserable beasts seemed to scent the freshness in the air, and they raised their heads and traveled more briskly. Within half a mile of the river the animals broke into a run in a stampede and refused to stop until they had plunged neck deep in the refreshing flood and when they were unyoked they snorted, tossed their heads and rolled over and over in the water.…after a journey of two thousand miles they raised heads and tails and galloped at full speed, an emigrant wagon with flapping sides jolting at their heels.” The Carson Sink gradually accumulated cattle carcasses and abandoned wagons left by travelers whose oxen had collapsed in the desert. A migrant then had no choice but to finish the trek on foot carrying what belongings he could on his back.

Based on the accounts of travelers on the California Trail it is clear it was a trip of hardship from the beginning. But the last segment crossing the Forty-mile Desert took a heavy toll. Most people managed to complete the crossing, but in a demoralized state. Regardless they had no choice but to press on to the next hurdle, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, another grueling episode requiring the last bit of energy from man and beast.

Sources

Bagley, Will. With Golden Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West 1849-1852. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2012.

Morgan, Dale L., The Humboldt: Highroad of the West. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 1943.

The California Trail,Part 1

The California Trail turned away from the Oregon Trail about sixty miles east of present day Idaho Falls, and headed southwest toward the beginning of the Humboldt River near present day Wells, Nevada. The source of the Humboldt River main stem in northeastern Nevada is a spring called Humboldt Wells. From that point the wagon trains headed westward following the Humboldt River to its end in the Humboldt Sink. This article covers the California Trail emigrants along the Humboldt River.

About 300 diaries written by migrants on the California Trail provide a wealth of insight into travel through the harsh and unfamiliar terrain of the Great Basin Desert, mostly within the present State of Nevada. Weeks of travel along the Humboldt River through scorching heat and stifling dust taxed the endurance of men, women, horses, mules, and oxen. The saving factor that made such a trip possible was the Humboldt River itself. The river provided water for most of the route across the Basin, and supported grass of variable quality along its shores. The diaries of those nineteenth century migrants give accounts of distances, quality of water and grass, and the general conditions and hardships the travelers faced. The following is a sampling written during crossings from 1849 to 1855 through the Great Basin.

One migrant, James Wilkins, expressed his strong opinion of the Great Basin, “…the most detestable countries God ever made, to say nothing of its sterility and barrenness.” The wagon trace followed the river for almost 300 miles, but for most migrants the trip seemed unending, partly because they had no certain way of knowing how much farther they had to go.

Often one wagon train was followed closely by others, sometimes creating a congestion of people. The route became so crowded at times that A.H. Houston wrote, “The immense crowd on the road made the trip more difficult and disagreeable. If you tried to pass other trains, you broke down your team in doing so. If you laid by to recruit, hundreds of teams were passing daily, making it more difficult to procure grass.” (The word “recruit” was commonly used in the nineteenth century meaning replenish or refresh.) Finding adequate grass for livestock was a daily problem. Some stretches of the trail offered good grass, but in many places grass was inadequate. Joseph Wood, lamenting the poor grass as his cattle began wasting away, wrote, “The grass does not contain sufficient nourishment for teams that have so much work to perform and hardships to endure.”

As they went downstream conditions grew worse daily. Charles Tinker: “Feed grew scarcer & water poorer & the weather hotter.” As the river water became more alkaline the travelers began to hate the river. Elisha Perkins wrote, “I must agree with the majority of the Emigrants in nicknaming it ‘Humbug River.” He added that the “river had become only a good sized creek. We could hardly get enough for our mules to eat and water barely drinkable from saline and sulfurous impregnation and having a milky color.”

Another constant problem was the six to ten inches of dust that lay on the trail raising choking clouds into the air. William Z. Walker wrote, “The dust along the stream in intolerable, filling our eyes so that we could hardly see our animals. We were visited by such a hurricane of dust during the forenoon that we were obliged to turn out of the road and stop till the wind subsided.” John Middleton added, “Our poor faded and exhausted cattle! It harrowed my soul that I could render them no relief—that we must rush on to save our lives at the expense of others. Poor obedient creatures, what hellish cruelties I have seen inflicted on them by hard-hearted men.” Unfortunately the travelers who arrived later in the summer found conditions worse because the grass had not sufficiently recovered from the passage of earlier wagon trains. Wagon wheels passing through the hot dust dried to the point that their wooden wheels rattled “like a bag of bones” as they turned. Not surprisingly many migrants had buyers remorse as conditions worsened. Joseph Wood wrote, “I would give One Dollar for a newspaper, Five for a letter and Fifty to see our friends. We shall be glad to leave the valley of the Humboldt.”

The marshy conditions at the terminus of the Humboldt River provided good stands of grass and the travelers stopped long enough to cut ample grass to carry for the perilous trek across the Carson Sink. Through August the grassy meadow was crowded with emigrants. Thomas van Dorn wrote, “Without this grass here, this route would be abandoned, but it forms a natural recruiting point in this vast desert region,”

Near today’s Lovelock, Nevada, the nearly depleted Humboldt River spread out into a vast playa and intermittent wetland called Humboldt Sink, now shown on maps as Humboldt Lake. This harsh dry lake bed, or playa, merged with another massive playa, the Carson Sink, formed at the terminus of the Carson River flowing from the Sierra Mountains. The two great playas were separated by a low, almost imperceptible, divide called the Humboldt Bar. The Carson Sink became known to migrants as “The Forty-mile Desert.” The scene on the Forty-mile Desert is bleak, flat, and featureless. The Carson Sink is visible as you speed by on Interstate 80 and one can only imagine crossing it on foot or in a slow-moving wagon.

Migrants often wrote of their disgust for conditions at the end of the Humboldt. Amasa Morgan lamented that, “This river that forces its way 290 miles through narrow Kanyans sandy deserts and around many a mountain here is lost in the earth, and whare its waters go to no one knows.” David Hindman called the area “a pool of black, stagnant water…upon which the stillness of death was resting.” A migrant named Addison Crane wrote a poem expressing his disdain for the Humboldt River:

Farewell to thee, thou stinking, turbid stream,

Amid who's waters frogs and serpents glean.

Thou putrid mass of filth, farewell forever.

At the Humboldt Bar the trail divided with one branch going northwest to the Truckee River and the other southeasterly to the Carson River. Both distances were about the same which most diaries estimate to be a little more than forty miles. Rumors and advice based on hearsay persuaded travelers that one or the other route would be better to take. Actually they were about equally bad. The Truckee route led to Donner Pass and the Carson route crossed the Sierra Nevada at Carson Pass. Crossing the Sierras is the subject of another blog. Before crossing the Forty-mile Desert, they first tried to prepare for their animals. They filled everything that could hold water—kegs, boilers, kettles, coffee pots, and rubber boots, and cut extra grass to carry over the desert expanse.

Joseph Berrien said the forty-five miles of desert had fifteen miles of heavy sand and advised, “Be careful to drive in the night. Expect to find the worst desert you ever saw and you will find it worse than you expected.” Thomas Evershed described his first impression of the Carson Sink as, “a beautiful sheet of water seemingly about a mile across with the reflections of the mountains in it. …it was a mirage, the first we had seen. Soon it disappeared, leaving not a trace behind except the carcass of an old ox. Oh! For a drink of good ice water.”

Whether traveling by day or night the Carson Sink was a perilous time for man and beast. One migrant wrote, “During the day our supply of water became exhausted. The teams began to fail. The roadside was almost covered with the carcasses of animals that could not make further progress and lay there.” When the animals died there was no way to pull the wagon, leaving many wagons abandoned along the roadside. They reported that the dead animals created “unsupportable stench, while the moans and creaky teeth of the yet living was enough to move a dragon to pity. Wagons abandoned by their owners are to be seen in every direction.”

Writing about the Forty-mile Desert crossing Luzena Wilson wrote, “It was a hard march over the desert. The men were tired of goading on the poor oxen which seemed ready to drop at every step. They were covered with a thick coating of dust, even the tongue which hung from their mouths was swollen with thirst and heat.” Wilson continued his description of the desert crossing and told of the change he saw as they neared the Carson River. “The miserable beasts seemed to scent the freshness in the air, and they raised their heads and traveled more briskly. Within half a mile of the river the animals broke into a run in a stampede and refused to stop until they had plunged neck deep in the refreshing flood and when they were unyoked they snorted, tossed their heads and rolled over and over in the water.…after a journey of two thousand miles they raised heads and tails and galloped at full speed, an emigrant wagon with flapping sides jolting at their heels.” The Carson Sink gradually accumulated cattle carcasses and abandoned wagons left by travelers whose oxen had collapsed in the desert. A migrant then had no choice but to finish the trek on foot carrying what belongings he could on his back.

Based on the accounts of travelers on the California Trail it is clear it was a trip of hardship from the beginning. But the last segment crossing the Forty-mile Desert took a heavy toll. Most people managed to complete the crossing, but in a demoralized state. Regardless they had no choice but to press on to the next hurdle, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, another grueling episode requiring the last bit of energy from man and beast.

Sources

Bagley, Will. With Golden Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West 1849-1852. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2012.

Morgan, Dale L., The Humboldt: Highroad of the West. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 1943.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed