Alkali flats on the Forty Mile Desert.

Alkali flats on the Forty Mile Desert. Crossing the driest part of present day Wyoming required carrying enough water to last the seventy miles to the Green River. Margaret Frink wrote that they began the first hazardous twenty-one mile stretch at five in the afternoon so they could travel in the cool of the evening and through the night. She described traveling at night: “the moon shone bright as day and we were in good spirits. A violinist played while others sang, and the long night passed very pleasantly.” They reached a small flowing tributary of the Green River about two A.M. They filled their five-gallon water bottles and stayed there until morning.

They still faced a forty-mile stretch of land with no water. Margaret Frink wrote, “At six o’clock [A.M.] we started being anxious to get to the Green River as soon as possible.” The wagons reached the west edge of the desert late in the day. From there they could see the Green River several miles ahead. But first they had to get all the wagons down from the bluffs and onto the river plain below. This feat required lowering the wagons cautiously with ropes while the people and animals walked down through narrow gorges on a layer of dust twelve to twenty inches deep. Clouds of blinding, choking dust rose as they passed through the gorges down to the river plain.

The plain below the bluffs was crowded with immigrants waiting to be ferried across the Green River by one of the two flatboats and rowed across by the ferrymen. Mrs. Frink tells that the poor horses had to swim across, and the water was “high, deep, swift, blue, and cold as ice.” The animals were reluctant to enter the water and one of the Frink’s animals utterly refused. The ferryman finally agreed, against his better judgement, to ferry that one horse across. The other animals had to be led behind the boat. After the crossing all the animals were allowed to rest and graze.

A disturbing development occurred the next day. Mr. Frink became ill with what she called “mountain fever” and could not walk. He climbed into the wagon with great difficulty and stayed in the bed. They could not make it onto the ferry and their wagon had to wait alone through the night. Margaret Frink told of her feeling of loneliness and helplessness a thousand miles from civilization. For the first time Mrs Frink mentions being frightened. The next morning Mr. Frink had improved somewhat but was still confined to his bed. They crossed the river in the afternoon, but were unable to proceed. After three days Mr. Frink began to improve, but Mrs. Frink called it “the darkest period of our whole journey.” After five days they began to travel again and went twelve miles, and their rate of progress returned to a “normal” twelve to twenty miles per day. In time they were able to rejoin the wagon train.

In two more weeks they passed a pool of soda water on a mound about five feet high near the site of present day Soda Springs, Idaho. They drove beside it and Mrs. Frink dipped a cup of soda water “without leaving my seat in the wagon. She learned later from other travelers that the soda water made a very light biscuit. [Note: the soda springs the immigrants encountered is a natural spring of carbonated water that is rich in sodium bicarbonate, i.e. baking soda, along with several other minerals derived from an underlying aquifer in lava beds.]

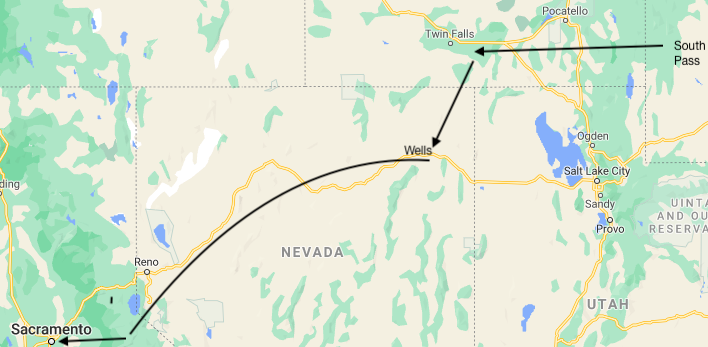

After several days of travel beyond the soda springs, Margaret Frink wrote about finally reaching the headwaters of the Humboldt River, the migrants highway across what is present day Nevada. Springs flowed from the ground and the grass was plentiful so they encamped for the night. From this point they knew water would be available for most of the 250 miles to the Humboldt Sink, an immense, barren, dry lake bed that they must cross…the so-called Forty Mile Desert.

After a few days following the Humboldt River, Mrs. Frink told what happened to the young boy, Robert, who traveled with them. “Robert took up a horse near the road, it having the appearance of being lost, and by so doing got separated from us.” Mrs. Frink was very anxious about the boy, but hoped he would find his way back to them. “I was almost frantic for fear the Indians had caught him.” This fear was increased when she heard from others that five hundred natives were camped nearby. When evening came, a man named Aaron Hill unhitched one of his horses and went back to look for Robert. By this time Margaret was distraught with fear that they would never find the boy. Soon after dark Aaron returned with Robert and Margaret wrote, “My fears turned into tears of joy.”

The trail along the Humboldt River sometimes detours away from the river because of obstructing bluffs. As the wagons moved away from the river they encountered choking dust and little grass. Other times they had no choice but to cross the river and travel on the other side. In one such instance Margaret told of some men who had cleverly made a raft using a wagon turned upside-down with some some empty kegs at each corner as floats. They loaded all the contents of their wagon on the makeshift raft and pulled it back and forth with ropes.

When they had finished, the raft builders kindly let the Frinks use the raft. Margaret wrote, “We piled our provisions, bedding, cooking utensils, hay, and all the other stuff, and after many trips got everything safely over. When I crossed, I sat with my feet in the wash-tub to keep them dry.” After harnessing the horses and loading the wagons, the Frinks traveled five miles farther before camping for the night.

Mrs. Frink told about encountering some Hungarians who had not eaten for two days. The Frinks could offer them little help as they were carefully rationing their own food supply, “…the situation looked gloomy to every one of us. They were crossing an extensive area of sand hills with no vegetation. They continued traveling until ten o’clock that night before the trail returned to the river. When they stopped for the night Margaret described, “a terrible scene, the earth was strewn with dead horses and cattle.” That night the horses poked their heads into the wagon and ate all the beans and dried fruit. “The poor animals had had nothing to eat except the short allowance of hay we had hauled with us.”

After traveling the Humboldt Valley for about 230 miles, Mrs. Frink wrote that they passed many dead animals and late in the day they arrived at an area called Big Meadows where they finally found some grazing for their livestock. Fortunately they found good grass for the next several miles. They stopped among many other immigrants all taking a short break to cut extra grass, make hay, and get ready to cross the dreaded Humboldt Desert, sometimes called the Forty Mile Desert. They expected to reach this dangerous stretch of trail—the worst of the entire journey—in the next two days. Today highway I-80 allows us to zip across this barren land in an easy hour of air-conditioned comfort, but I cannot make that trip without trying to imagine what it would be like in a covered wagon. Their only relief was to travel at night to avoid the August sun.

To add to the Frink’s anxiety were many stories of horrible things that had happened to previous travelers across this waterless wasteland. They heard stories about great losses of horses, mules, and oxen during the dangerous crossing. Naturally they had no certainty that their own animals would survive the crossing. By the time the Humboldt River reached this area the water became brackish and discolored from alkali. Margaret Frink described the water as having the color and taste of “dirty soap-suds.” Nevertheless, people and animals drank it out of necessity. They now must leave the river and travel about seventy miles without replenishing their water.

They began the feared crossing of the immense dry lake bed long before sunrise and at six they stopped to rest for four hours. At ten o’clock they started again and soon began see horrible sights. Margaret wrote that “Horses, mules, and oxen suffering from heat, thirst and starvation staggered along until they fell and died. Both sides of the road for miles were lined with dead animals and abandoned wagons. Around them were strewn yokes, harnesses, guns, tools, bedding, clothing, cooking-utensils all in utter confusion.” Many immigrants had left everything except what they could carry on their backs and pushed ahead to try to save themselves.

No one in the Frink group stopped to look or help. It was all anyone could do to save themselves and their animals. As they proceeded, the situation became more dreadful and dead animals became more numerous. The stench of their carcasses filled the hot August air.

Careful forethought and planning saved the Frinks. They avoided the mistakes made by many immigrants who tried to travel too fast and exhausted their animals. The Frinks had cut a good supply of grass and made hay in the meadows before the sink. They carried a few gallons of water for each animal, traveled slowly and rested often. Many other immigrant parties traveled the worst part at night to avoid traveling in the heat.

Surprisingly, the Frinks met a wagon carrying barrels of pure, sweet water from a spring about five miles south of the road. The Frinks bought one gallon of the water for $1.00 (about $33 in today’s dollars) and deemed it a refreshing luxury.

At eleven o’clock at night on August 17th, the Frinks reached the Carson River after thirty-seven hours crossing the most treacherous desert of their journey. They had come through without any loss of animals or property, but thoroughly exhausted. The Carson River valley was abounding in good water and pastures, and those who reached this point were then only one hundred miles from Sutter’s Fort. Many of the immigrants at this point were clothed in tatters and many traveled on foot, having lost their animals. Most of the people they met were in ragged clothing and near starvation. Mrs. Frink told of one man they met who had lost everything. “He was without shoes and his feet were tied up in rags. The only food he had was one pint of corn meal. I made him a dish of gruel with some butter and other nourishing things.”

Of course the Sierra Nevada Mountains still stood between them and their destination. Although the mountains require very strenuous labor they are not a serious hazard if crossed early enough. The Donner party had already demonstrated the potential danger with serious loss of life when they tried to cross the mountains in late October, 1846.

Crossing the mountains involved steep, rough roads, and in many places deep, hard-packed snow still covered the ground. In especially steep places immigrants joined effort by loaning horses to one another so they could double team over the most difficult parts. In these places long ropes were tied to the tongue of the wagon and the men helped pull along with the horses. Others worked beside the wheels and pulled on the spokes. They also had to be prepared to block the wheels when the wagon stopped to prevent it from rolling back. In places the immigrants had to unharness their horses and hoist the wagons over a bluff while the horses walked around it on a path too rough or too narrow for wagons.

By five o’clock that day they had reached the main ridge of the Sierra Nevada after ten hours of struggle. “The worst is now over,” wrote a relieved and exhausted Margaret Frink. Now they were in settled country again. Mrs. Frink wrote of passing trading posts with fruits and vegetables at exorbitant prices. They passed Sutter’s Fort just east of Sacramento. At last! They had arrived! Margaret noted that they had traveled 2418 miles in five months and seven days.

In case you missed the first blog about the Frink’s housing plan, the following is a recap of Mr. Frink having a ready-to-assemble house built in Indiana and shipped to San Francisco:

His (Mr. Frink’s) pre-cut lumber went by boat down the Wabash River to the Ohio, then to the Mississippi, all the way to New Orleans where it was loaded on a ship headed around the horn to San Francisco. Travel time by water from Indiana to San Francisco around the Horn in 1850 was at least one hundred days plus time for transferring the load from a river boat to a sailing ship.

The pre-cut lumber for their house was waiting for them when they arrived in California and it was erected in a few days. Margaret Frink died in 1893 at the age of seventy-five. In 1897 Mr. Frink decided to have her extensive diary published as a book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed