After several starts described in Part 1, Parkman and his party finally began to make progress, or so they thought. … After only two hours they came to a trading post where the owner informed them they were headed in the wrong direction and they had made no westward progress. They also discovered that no one in the party actually knew the way.

A few rather emphatic exclamations might have been heard

among us, when we found that we had gone miles out of our way,

and had not advanced an inch toward the Rocky Mountains. So

we turned in the direction the trader indicated, and with the sun

for a guide, began to trace a “bee line” across the prairies.

The next day brought another delay when one of Parkman’s horses decided to head back home to Kansas City. As they stopped for noon and took the horses to a nearby stream:

…my homesick charger, Pontiac, made a sudden leap, and set

off at a round trot for the settlements. I mounted my remaining

horse, and started in pursuit. Making a circuit, I headed the

runaway, hoping to drive him back to camp; but he instantly

broke into a gallop, made a wide tour on the prairie, and got

past me again. …The chase grew interesting. For mile after mile

I followed the rascal.

Old Pontiac eluded capture for hours and when Parkman finally caught him they had to travel miles to catch up with rest of the group.

(Note: My own impression of the prairie terrain east of Manhattan,Kansas is one of stunning beauty; an endless sea of thick grassland blown into undulating waves by the wind. Parkman was no less impressed.)

The scenery, though tame, is graceful and pleasing. Here are

level plains, too wide for the eye to measure green undulations,

like motionless swells of the ocean; abundance of streams,

followed through all their windings by lines of woods and

scattered groves.

Nevertheless that beautiful land found a way to make his life a little harder. From his experience to date he now expected things to go wrong. Consequently, Parkman warned against being fooled by the scenery.

But let him be as enthusiastic as he may, he will find enough to

damp his ardor. His wagons will stick in the mud; his horses will

break loose; harness will give way, and axle-trees prove

unsound. His bed will be a soft one, consisting often of black mud,

of the richest consistency.

In the last half of the nineteenth century one prominent presence on the trail was the Mormon migration to Utah. They had an unsavory reputation for disliking outsiders and were somewhat feared for their clannishness. Many considered them dangerous. Parkman gave some insight to the issue:

We had heard reports that several additional parties were setting

out from St. Joseph (Missouri) farther to the northward. The

prevailing impression was that these were Mormons,

twenty-three hundred in number; and a great alarm was

excited in consequence. The people of Illinois and Missouri, who

composed by far the greater part of the emigrants, have never

been on the best terms with the “Latter Day Saints” and it is

notorious throughout the country how much blood has been

spilt in their feuds, even far within the limits of the settlements.

No one could predict what would be the result, when large

armed bodies of these fanatics should encounter the most

impetuous and reckless of their old enemies on the broad

prairie, far beyond the reach of law or military force.

As with many rumors they had no factual basis. In fact the group in question were not Mormons at all. Parkman adds that, “The St. Joseph’s emigrants were as good Christians and as zealous Mormon-haters as the rest.” It is no surprise that even Christians need someone to hate.

As beautiful as the prairie grassland was, it was not without hazards for the migrants. One problem was the infrequency of streams for watering livestock and replenishing water kegs. Because there are few streams there are also few trees for firewood.

(Note: As farmers began to settle this vast prairie, they faced a lack of wood for fence posts. Their solution was limestone posts for their barbed wire fences. Today most limestone posts are replaced with steel posts, but some stone posts remain and can be seen as you speed along highway I-70 through the Flint Hills of Kansas.) Parkman’s group faced this shortage and described their firewood dilemma:

One day we rode on for hours, without seeing a tree or a bush;

before, behind, and on either side, stretched the vast expanse,

rolling in a succession of graceful swells, covered with the

unbroken carpet of fresh green grass. Here and there a crow,

or a raven, or a turkey-buzzard, relieved the uniformity. “What

shall we do to-night for wood and water?” we began to ask of

each other; for the sun was within an hour of setting. At length

a dark green speck appeared, far off on the right; it was the

top of a tree, peering over a swell of the prairie; and leaving the

trail, we made all haste toward it. It proved to be the vanguard

of a cluster of bushes and low trees, that surrounded some

pools of water in an extensive hollow; so we encamped on the

rising ground near it.

Upon reaching the water they immediately had another problem.

…it was four feet deep; we lifted a specimen in our cupped

hands; it seemed reasonably transparent, so we decided that

the time for action was arrived. But our ablutions were

suddenly interrupted by ten thousand punctures, like poisoned

needles, and the humming of myriads of over-grown

mosquitoes, rising in all directions from their native mud and

slime and swarming to the feast. We were fain to beat a retreat

with all possible speed.

It has become clear by now that Parkman’s journey was filled with mishap and error. Even though there were experienced men with him the troubles continued. I have read of no other expedition that had so many things go wrong with equipment and livestock. The next near-disaster involved all their horses heading for home again. It began the next morning:

…we had just taken our seats at breakfast, when the captain gave

a shout of alarm. …looking up, we saw the whole band of animals,

twenty-three in number, filing off for the settlements (meaning

Westport), the incorrigible Pontiac at their head, jumping along

with hobbled feet, at a gait much more rapid than graceful. Three

or four of us ran to cut them off, dashing as best we might through

the tall grass, which was glittering with myriads of dewdrops.

After a race of a mile or more, Shaw caught a horse. Tying the

trail-rope by way of bridle round the animal’s jaw, and leaping

upon his back, he got in advance of the remaining fugitives, while

we, soon bringing them together, drove them in a crowd up to the

tents, where each man caught and saddled his own. Then we

heard lamentations and curses; for half the horses had broken

their hobbles, and many were seriously galled (chafed) by

attempting to run in fetters.

Parkman again described the beauty and the harshness of the open prairie:

Not a breath of air stirred over the free and open prairie; the

clouds were like light piles of cotton; and where the blue sky

was visible, it wore a hazy and languid aspect. The sun beat

down upon us with a sultry penetrating heat almost insupportable,

and as our party crept slowly along over the interminable level,

the horses hung their heads as they waded fetlock deep

through the mud, and the men slouched into the easiest position

upon the saddle. At last, toward evening, the old familiar black

heads of thunderclouds rose fast above the horizon, and the

same deep muttering of distant thunder that had become the

ordinary accompaniment of our afternoon’s journey began to

roll hoarsely over the prairie. Only a few minutes elapsed

before the whole sky was densely shrouded, and the prairie

and some clusters of woods in front assumed a purple hue

beneath the inky shadows. Suddenly from the densest fold of

the cloud the flash leaped out, quivering again and again down

to the edge of the prairie; and at the same instant came the

sharp burst and the long rolling peal of the thunder. A cool

wind, filled with the smell of rain, just then overtook us,

leveling the tall grass by the side of the path. …The whole

party broke into full gallop, and made for a cluster of trees.

We rode pell-mell upon the ground, leaped from horseback,

tore off our saddles; and hobbled the horses and set up

tents…just as the storm broke. It came upon us in roaring

torrents of rain. ...Supper that night was out of the question.

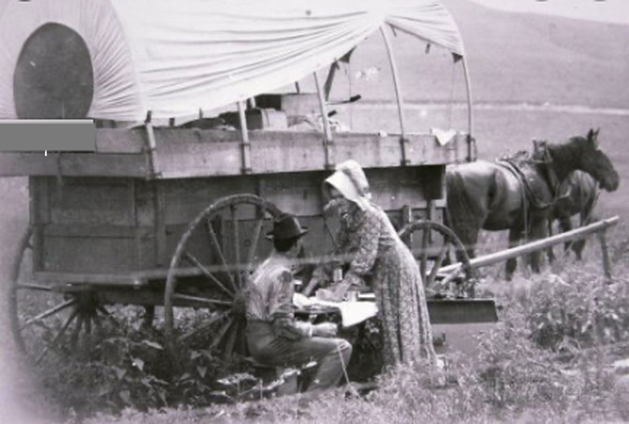

Despite one mishap after another Parkman pushed ahead. Clearly his motivation was decidedly different from the typical westward migrant. Typical migrants had staked their entire future on the success of their hard, long journey. Most of them had no option for return because they had literally sold the farm to start a new life. Parkman on the other hand made the journey out of curiosity. He had no intention of staying in Oregon and expected to return to his comfortable life in upperclass Boston.

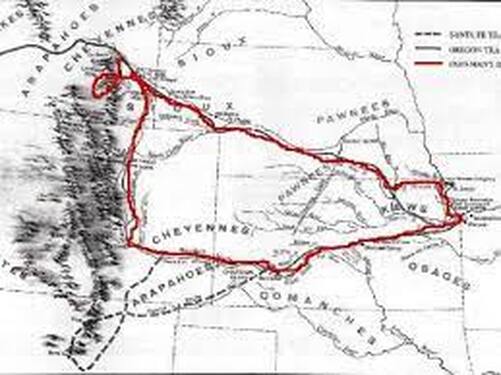

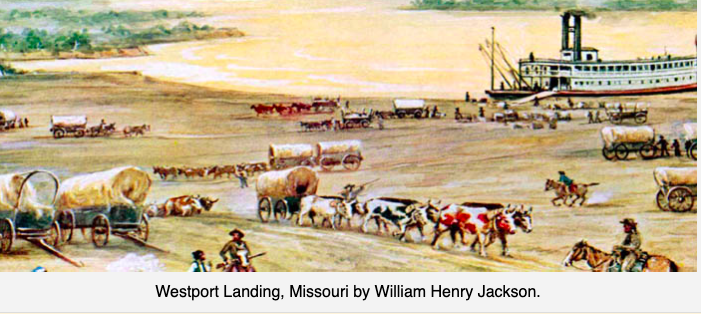

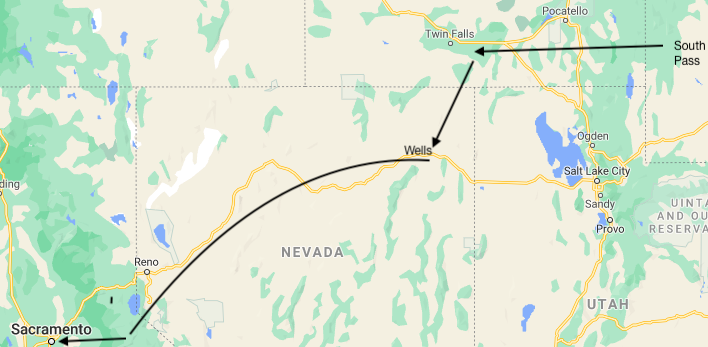

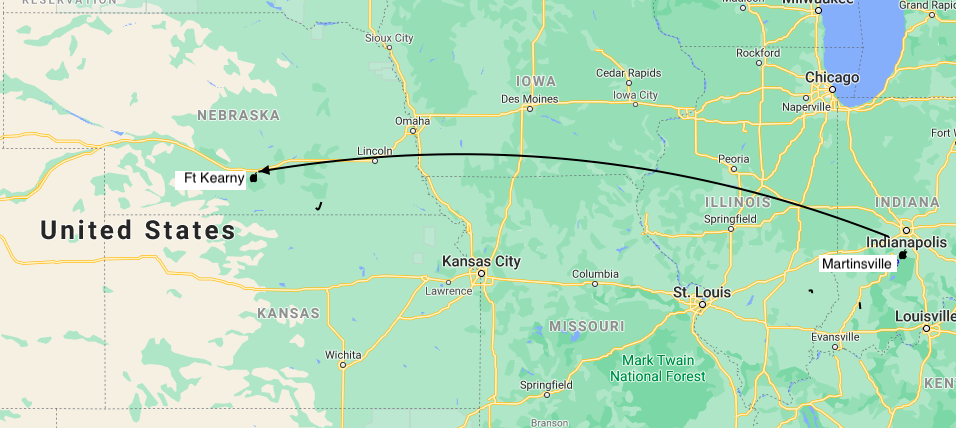

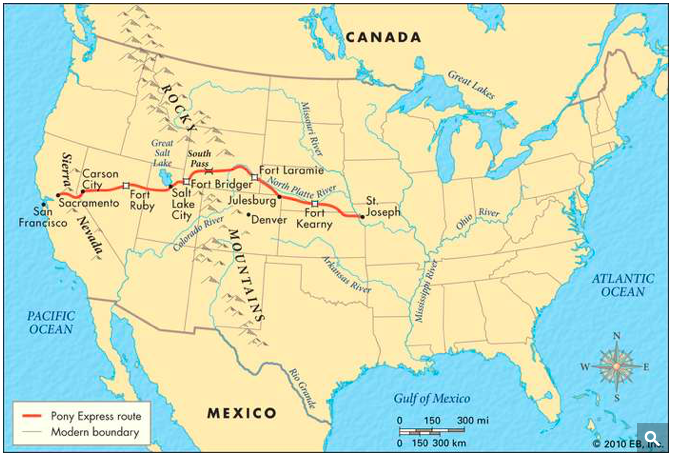

Unlike most migrants on the Oregon Trail Francis Parkman turned back long before reaching Oregon. His route followed the Platte River through the land now called Nebraska and Wyoming as far as Fort Laramie. From there he traveled south past the future site of Denver to Fort Pueblo on the Arkansas River which he then followed to Fort Dodge. From there he followed the Santa Fe Trail back to Westport, Missouri. The narrative describes their steady progress, friendly meetings with Indians, and frequent accidents.

While researching material about Parkman I noted he often wrote disparagingly about most of the other travelers he encountered. He described most migrants, mainly farmers, as low-class and lacking intelligence. He wondered how they could possibly think their lives were going to be better in Oregon. He questioned why they would even bother going through such a hard journey with so little hope of a real change in their lives. Indians he saw in Westport held an even lower position in his mind and he described them as “ugly" and “dirty.” When he finally encountered Indians on the prairies his opinion improved as they looked to him a bit more intelligent and clean. Over all, Parkman simply cannot hide his privileged, patrician background. Granted, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries derogatory speech about other races and outspoken feelings about white superiority were usually accepted as normal. This nineteenth-century attitude makes Parkman’s prejudiced statements stand out starkly today.

Indian news sources especially have noticed. I saw a review of Parkman in an online news service called “Indian Country Today.” The title pretty much summarizes their opinion: “Native History Meets Human Arrogance: Privileged Author Begins Study of "Manners and Characters of the Indians in their Primitive State.” (The quote is the title of one of Parkman’s articles.)

Nevertheless, Parkman’s “Oregon Trail” still remains an important resource about the western lands and the native tribes just before European settlement began.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed