This undated photo shows a young Parkman, probably taken near the time of his trip on the Oregon Trail.

This undated photo shows a young Parkman, probably taken near the time of his trip on the Oregon Trail. Roger M McCoy

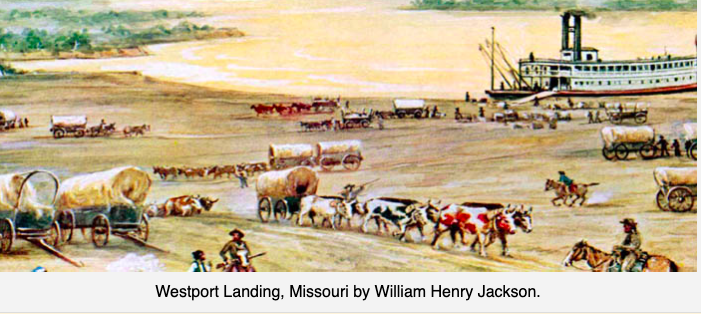

“The Oregon Trail” by Francis Parkman makes it clear that expeditions across the west had great potential for mistakes and accidents. The migrants on western trails must have had some first-day thoughts…anticipation? hope? anxiety? apprehension? regret? They took such a tremendous leap into unknown territory and into an unfamiliar new life. Parkman’s account gives many insights that most travelers’ diaries do not, and it has been widely read since its first publication in 1847. He writes a vivid image of the hustle and busyness of river port cities and assembly points such as St. Louis, Independence, and Westport, Missouri.

Francis Parkman was not an emigrant, rather he was making a trip to hunt and to satisfy his curiosity as a trained historian. He entered Harvard at age sixteen and after graduation entered law school. The son of a wealthy Boston family, Parkman had sufficient money to pursue his interests without concern about finances. In addition his income was supplemented by royalties from books he authored. He traveled across North America, visiting most of the historical locations he wrote about, and made frequent trips to Europe seeking original documents with which to further his research.

In the spring of 1846 Francis Parkman, with “friend and relative” Quincy Shaw, left St. Louis in a river steamboat loaded with emigrants, merchandise, mules, horses and “a multitude of nondescript articles.” In a boat that was “loaded until the water broke alternately over her guards.” He wrote that the heavily loaded river steamer, “struggled upward for seven or eight days against the rapid current of the Missouri River, grating upon snags, and hanging for two or three hours at a time upon sand-bars.” He wrote a vivid description of the overloaded riverboat and its array of passengers.

Her upper deck was covered with large weapons of a peculiar

form, for the Santa Fe trade, and her hold was crammed with

goods for the same destination. There were also the gear and provisions of a party of Oregon emigrants; a band of mules and horses, piles of saddles and harness, and a multitude of

nondescript articles, indispensable on the prairies. …In the

boat’s cabin were Santa Fe traders, gamblers, speculators,

and adventurers of various descriptions, and her steerage was crowded with Oregon emigrants and “mountain men,” negroes,

and a party of Kansas Indians, who had been on a visit to

St. Louis.

As they neared Independence, Missouri, Parkman “began to see signs of the great western movement that was then taking place. Parties of emigrants, with their tents and wagons, would be encamped on open spots near the bank, on their way to the common rendezvous at Independence.” Parkman conveys a clear picture of the excitement and anticipation among the accumulation of travelers waiting to begin their overland journey…traders headed for Santa Fe, immigrants to far-off California or Oregon, Indians returning to Mexico, French hunters from the mountains with their long hair and buckskin dress.

Independence was a port city on the river and for emigrants it was the beginning of a 2,170 mile wagon journey to the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Imagine the crowds of people debarking the boat in Independence in anticipation for a new life in a new land. From the Independence docks they traveled overland about twelve miles to Westport, Missouri where they bought mules, horses, wagons, and provisions. Westport at that time was on the western edge of the United States, and the starting point for most westward travelers whether headed to Santa Fe, California, or Oregon. What is now Kansas was still seven years from designation as a territory of the United States.

In Westport Parkman met a Scot, identified only as Captain C., who had been in the British Army, his brother (unnamed), and Mr. R., an Englishman. For reasons of safety and mutual support they decided to join forces and travel to Oregon together. In addition, Captain C. had employed a Canadian hunter named Delorier and an American [unnamed] as a muleteer. Captain C. had already acquired a number of horses and mules for packing provisions.

One day while waiting for departure Parkman went to Westport and described the high activity in the city:

The town was crowded. A multitude of shops had sprung

up to furnish the emigrants and traders with necessaries

for their journey; and there was an incessant hammering

and banging from a dozen blacksmiths’ sheds, where the

heavy wagons were being repaired, and the horses and

oxen shod. The streets were thronged with men, horses,

and mules. While I was in the town, a train of emigrant

wagons from Illinois passed through, to join the camp on

the prairie, and stopped in the principal street. A multitude

of healthy children’s faces were peeping out from under

the covers of the wagons. … Whisky by the way circulates

more freely in Westport than is altogether safe in a place

where every man carries a loaded pistol in his pocket.

Parkman tended to show a low regard for most immigrants, and his comments on them was often disparaging. He especially showed disdain for the uneducated farmers hoping for a new life, Germans, French, Blacks, and Indians. For instance he expressed doubts that some of them could actually believe they would have better lives elsewhere.

Among them are some of the vilest outcasts in the country.

I have often perplexed myself to divine the various motives

that give impulse to this strange migration; but whatever

they may be, whether an insane hope of a better condition

in life, or a desire of shaking off restraints of law and society,

or mere restlessness, certain it is that multitudes bitterly

repent the journey, and after they have reached the land

of promise are happy enough to escape from it.

Remember Parkman came from a prominent Boston family and probably had little contact with other types of people who populated the midwestern and southern states.

After eight days of preparation in Westport, Parkman and his traveling companions were ready to embark with their wagon and animals. A few days into Kansas Territory they were hit by an intense thunderstorm. Anyone from the midwest has seen such terrific storms.

We were leading a pair of mules to Kansas when the storm

broke. Such sharp and incessant flashes of lightning, such

stunning and continuous thunder, I have never known before.

The woods were completely obscured by the diagonal sheets

of rain that fell with a heavy roar, and rose in spray from the

ground; and the streams rose so rapidly that we could hardly

ford them.

The storm caused them to return “drenched and bedraggled” the few miles back to Westport. Unfortunately the onset of his long journey was beset by false starts and needless mishaps. A few days later, with clear weather and renewed provisions, they made another near-disastrous beginning. “No sooner were our animals put in harness, than one mule reared and plunged, burst ropes and straps, and nearly flung the cart into the Missouri.” Not long after that experience their wagon became mired in “a deep muddy gully” that delayed them for another hour. Surprisingly this bad beginning left Parkman undiscouraged and determined to continue forward.

Parkman gives good descriptions of the men he hired for the trip. He described the hunter and guide, Henry Chatillon, as a rather dour character who:

wore a white blanket-coat, a broad hat of felt, moccasins,

and pantaloons of deerskin, ornamented along the seams

with rows of long fringes. His knife was stuck in his belt; his

bullet-pouch and powder-horn hung at his side, and his rifle

lay before him, resting against the high pommel of his saddle,

which, like all his equipment, had seen hard service, and was

much the worse for wear.

Unlike Chatillon, the Canadian hunter, Delorier, was a man of pleasant character who worked hard and maintained a cheerful disposition in the most difficult times as shown by Parkman’s description:

Neither fatigue, exposure, nor hard labor could ever impair

his cheerfulness and gayety, or his politeness to his bourgeois;

and when night came he would sit down by the fire, smoke his

pipe, and tell stories with the utmost contentment. In fact, the

prairie was his congenial element.

A few hours’ ride brought them to the banks of the Kansas River. They passed through the woods that lined the river and encamped not far from the bank. Finally after several beginnings to their trip Parkman wrote, “Our tent was erected for the first time on a meadow close to the woods, and the camp preparations being complete we began to think of supper.” Then Parkman took his rifle and went to hunt for dinner.

A multitude of quails were plaintively whistling in the woods and meadows; but nothing appropriate to the rifle was to be seen,

except three buzzards, seated on the spectral limbs of an old

dead sycamore, their ugly heads drawn down between their

shoulders. …as they offered no epicurean temptations, I

refrained from disturbing their enjoyment; and contented myself

with admiring the calm beauty of the sunset. …and the river,

eddying swiftly in deep purple shadows between the impending

woods, formed a wild but tranquilizing scene. [One hopes the hired hunters had better results.]

At last Parkman and his group were underway and headed for Oregon.

Source:

Parkman, Francis, The Oregon Trail. Heritage Press, 1943. (original publication 1849.)

“The Oregon Trail” by Francis Parkman makes it clear that expeditions across the west had great potential for mistakes and accidents. The migrants on western trails must have had some first-day thoughts…anticipation? hope? anxiety? apprehension? regret? They took such a tremendous leap into unknown territory and into an unfamiliar new life. Parkman’s account gives many insights that most travelers’ diaries do not, and it has been widely read since its first publication in 1847. He writes a vivid image of the hustle and busyness of river port cities and assembly points such as St. Louis, Independence, and Westport, Missouri.

Francis Parkman was not an emigrant, rather he was making a trip to hunt and to satisfy his curiosity as a trained historian. He entered Harvard at age sixteen and after graduation entered law school. The son of a wealthy Boston family, Parkman had sufficient money to pursue his interests without concern about finances. In addition his income was supplemented by royalties from books he authored. He traveled across North America, visiting most of the historical locations he wrote about, and made frequent trips to Europe seeking original documents with which to further his research.

In the spring of 1846 Francis Parkman, with “friend and relative” Quincy Shaw, left St. Louis in a river steamboat loaded with emigrants, merchandise, mules, horses and “a multitude of nondescript articles.” In a boat that was “loaded until the water broke alternately over her guards.” He wrote that the heavily loaded river steamer, “struggled upward for seven or eight days against the rapid current of the Missouri River, grating upon snags, and hanging for two or three hours at a time upon sand-bars.” He wrote a vivid description of the overloaded riverboat and its array of passengers.

Her upper deck was covered with large weapons of a peculiar

form, for the Santa Fe trade, and her hold was crammed with

goods for the same destination. There were also the gear and provisions of a party of Oregon emigrants; a band of mules and horses, piles of saddles and harness, and a multitude of

nondescript articles, indispensable on the prairies. …In the

boat’s cabin were Santa Fe traders, gamblers, speculators,

and adventurers of various descriptions, and her steerage was crowded with Oregon emigrants and “mountain men,” negroes,

and a party of Kansas Indians, who had been on a visit to

St. Louis.

As they neared Independence, Missouri, Parkman “began to see signs of the great western movement that was then taking place. Parties of emigrants, with their tents and wagons, would be encamped on open spots near the bank, on their way to the common rendezvous at Independence.” Parkman conveys a clear picture of the excitement and anticipation among the accumulation of travelers waiting to begin their overland journey…traders headed for Santa Fe, immigrants to far-off California or Oregon, Indians returning to Mexico, French hunters from the mountains with their long hair and buckskin dress.

Independence was a port city on the river and for emigrants it was the beginning of a 2,170 mile wagon journey to the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Imagine the crowds of people debarking the boat in Independence in anticipation for a new life in a new land. From the Independence docks they traveled overland about twelve miles to Westport, Missouri where they bought mules, horses, wagons, and provisions. Westport at that time was on the western edge of the United States, and the starting point for most westward travelers whether headed to Santa Fe, California, or Oregon. What is now Kansas was still seven years from designation as a territory of the United States.

In Westport Parkman met a Scot, identified only as Captain C., who had been in the British Army, his brother (unnamed), and Mr. R., an Englishman. For reasons of safety and mutual support they decided to join forces and travel to Oregon together. In addition, Captain C. had employed a Canadian hunter named Delorier and an American [unnamed] as a muleteer. Captain C. had already acquired a number of horses and mules for packing provisions.

One day while waiting for departure Parkman went to Westport and described the high activity in the city:

The town was crowded. A multitude of shops had sprung

up to furnish the emigrants and traders with necessaries

for their journey; and there was an incessant hammering

and banging from a dozen blacksmiths’ sheds, where the

heavy wagons were being repaired, and the horses and

oxen shod. The streets were thronged with men, horses,

and mules. While I was in the town, a train of emigrant

wagons from Illinois passed through, to join the camp on

the prairie, and stopped in the principal street. A multitude

of healthy children’s faces were peeping out from under

the covers of the wagons. … Whisky by the way circulates

more freely in Westport than is altogether safe in a place

where every man carries a loaded pistol in his pocket.

Parkman tended to show a low regard for most immigrants, and his comments on them was often disparaging. He especially showed disdain for the uneducated farmers hoping for a new life, Germans, French, Blacks, and Indians. For instance he expressed doubts that some of them could actually believe they would have better lives elsewhere.

Among them are some of the vilest outcasts in the country.

I have often perplexed myself to divine the various motives

that give impulse to this strange migration; but whatever

they may be, whether an insane hope of a better condition

in life, or a desire of shaking off restraints of law and society,

or mere restlessness, certain it is that multitudes bitterly

repent the journey, and after they have reached the land

of promise are happy enough to escape from it.

Remember Parkman came from a prominent Boston family and probably had little contact with other types of people who populated the midwestern and southern states.

After eight days of preparation in Westport, Parkman and his traveling companions were ready to embark with their wagon and animals. A few days into Kansas Territory they were hit by an intense thunderstorm. Anyone from the midwest has seen such terrific storms.

We were leading a pair of mules to Kansas when the storm

broke. Such sharp and incessant flashes of lightning, such

stunning and continuous thunder, I have never known before.

The woods were completely obscured by the diagonal sheets

of rain that fell with a heavy roar, and rose in spray from the

ground; and the streams rose so rapidly that we could hardly

ford them.

The storm caused them to return “drenched and bedraggled” the few miles back to Westport. Unfortunately the onset of his long journey was beset by false starts and needless mishaps. A few days later, with clear weather and renewed provisions, they made another near-disastrous beginning. “No sooner were our animals put in harness, than one mule reared and plunged, burst ropes and straps, and nearly flung the cart into the Missouri.” Not long after that experience their wagon became mired in “a deep muddy gully” that delayed them for another hour. Surprisingly this bad beginning left Parkman undiscouraged and determined to continue forward.

Parkman gives good descriptions of the men he hired for the trip. He described the hunter and guide, Henry Chatillon, as a rather dour character who:

wore a white blanket-coat, a broad hat of felt, moccasins,

and pantaloons of deerskin, ornamented along the seams

with rows of long fringes. His knife was stuck in his belt; his

bullet-pouch and powder-horn hung at his side, and his rifle

lay before him, resting against the high pommel of his saddle,

which, like all his equipment, had seen hard service, and was

much the worse for wear.

Unlike Chatillon, the Canadian hunter, Delorier, was a man of pleasant character who worked hard and maintained a cheerful disposition in the most difficult times as shown by Parkman’s description:

Neither fatigue, exposure, nor hard labor could ever impair

his cheerfulness and gayety, or his politeness to his bourgeois;

and when night came he would sit down by the fire, smoke his

pipe, and tell stories with the utmost contentment. In fact, the

prairie was his congenial element.

A few hours’ ride brought them to the banks of the Kansas River. They passed through the woods that lined the river and encamped not far from the bank. Finally after several beginnings to their trip Parkman wrote, “Our tent was erected for the first time on a meadow close to the woods, and the camp preparations being complete we began to think of supper.” Then Parkman took his rifle and went to hunt for dinner.

A multitude of quails were plaintively whistling in the woods and meadows; but nothing appropriate to the rifle was to be seen,

except three buzzards, seated on the spectral limbs of an old

dead sycamore, their ugly heads drawn down between their

shoulders. …as they offered no epicurean temptations, I

refrained from disturbing their enjoyment; and contented myself

with admiring the calm beauty of the sunset. …and the river,

eddying swiftly in deep purple shadows between the impending

woods, formed a wild but tranquilizing scene. [One hopes the hired hunters had better results.]

At last Parkman and his group were underway and headed for Oregon.

Source:

Parkman, Francis, The Oregon Trail. Heritage Press, 1943. (original publication 1849.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed