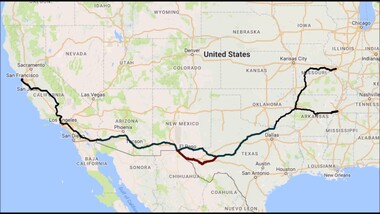

The Butterfield stage route originated from Saint Louis with a later branch to Memphis.

The Butterfield stage route originated from Saint Louis with a later branch to Memphis. Roger M McCoy

The first mention of a coach was in an English manuscript from the thirteenth century. The first known stagecoach route in Britain began much later, in 1610, and made a short run from Edinburgh to Leith, Scotland a distance of only three miles. This small beginning was soon followed by a proliferation of other routes, and by the mid-seventeenth century, a basic stagecoach infrastructure was in place in Great Britain. With infrastructure in place the stagecoach then became the primary means of carrying mail and passengers between cities. In 1649 Edward Chamberlayne wrote admiringly about this new transportation in England.

“Besides the excellent arrangement of conveying men and letters on horseback, there is of late such an admirable commodiousness, both

for men and women, to travel from London to the principal towns in

the country, that the like hath not been known in the world, and that

is by stage-coaches, wherein any one may be transported to any

place, sheltered from foul weather and foul ways; free from

endamaging of one's health and one's body by the hard jogging

or over-violent motion; and this not only at a low price (about a shilling*

for every five miles), but with such velocity and speed in one hour, as

that the posts in some foreign countries make in a day.”

(*NOTE: One shilling in 1650 was equivalent to $8.25 in today’s dollar. Today a shuttle from my house to the Tucson airport costs $49 or about $10 for every five miles. Coincidentally, that shuttle is called Stagecoach Express.)

In support of this growth in stage lines, coaching inns developed as stopping points for travelers on longer routes as between London and Liverpool. These inns became stopping points or stages in the journey that provided food and drink for the passengers and a change of horses. The business of running stagecoaches or the act of journeying in them was known as staging—hence the name stagecoach.

During the American colonial period, the stagecoach was the primary carrier among the New England colonies. In the early nineteenth century railroads began to be built in the United States and by 1845 were built as far west as Saint Louis, but there was still no way to send mail to San Francisco except by a long voyage by ship around South America.

In 1850 a ship from New York took about 200 days (6.5 months) to sail to San Francisco. The discovery of gold in California led to a rapid increase in population in the west and created a strong need for a shorter communication time with the west coast. To this purpose the United States Congress authorized a contract in 1857 for overland mail service from Missouri to California via horse-drawn conveyances. This far-reaching contract was awarded to New York businessman John Butterfield.

The visionary John Butterfield developed a grand scheme for a stagecoach route to carry mail and passengers from the railhead in Saint Louis to San Francisco in only twenty-five days. It took a year to work out the details, and Butterfield decided on a southern route, south from Saint Louis via Arizona to avoid bad weather. In addition, he refused to carry gold or silver in an effort to cut down on attacks by highwaymen. Butterfield built 139 relay stations along the 2,795-mile route, about twenty miles apart with meals and horses at each of the stops. For the twenty-five-day trip, the Butterfield stages did not stop for the passengers to sleep. Their only choice was to sleep on the moving stage.

In New Mexico and Arizona the Butterfield trail passed through Apache territory, and for two years the Chiricahua Apaches permitted safe passage by an agreement under which the tribe would be compensated and also provide firewood for the stage stations. This arrangement came to an end when an army lieutenant had an angry exchange of words with the Apache chief, Cochise, and the lieutenant put Cochise in jail. This unfortunate event led to hostilities between Apaches and Arizona settlers for the next twenty-five years.

In 1860 the Pony Express, a single rider on horseback, began carrying mail over a central route and shortened mail delivery time even further. The following year, the Butterfield Overland Mail route was discontinued and the Pony Express joined forces with Wells Fargo, which began in 1852 as an express and banking service.

Stagecoaches became such a fixture for travel that it is worth looking at them in some detail. Among several variations and sizes of stagecoach, two stand out as most used in the western United States. One was the Concord Coach, originally built in Concord, New Hampshire. This coach could hold six passengers inside with a few more sitting on top. Usually four horses were sufficient, but often six were used. The inside of the Concord style coach measured four feet wide and about four and one-half feet high. The seats were boards with padded leather upholstery, which were said to be harder than a bare board. The walls had cloth coverings.

A second type of stagecoach, built in Concord and Albany, was the celerity (swift) wagon. This lighter-weight wagon was designed by John Butterfield for use on his mail route. To decrease weight, the celerity wagon had canvas instead of a wooden top and larger window openings with canvas roll-down curtains. The larger windows reduced weight but gave less protection from constant dust. For extra stability the wheels were farther apart with longer axles. Wider steel rims on the wheels served well for traveling on sandy roads. Some stagecoaches had seat backs that let down to create a flat bed so passengers could sleep. However this feature was of limited use if the coach was full of people. Luggage was stored in a compartment on the back as the canvas roof could not bear weight.

One Butterfield passenger, a Mr. Ormsby, wrote in 1858 about his efforts to get some sleep while bouncing along in a celerity wagon. “Perhaps the jolting will be disagreeable at first, but a few nights without sleeping will obviate that difficulty, and soon the jolting will be as little disturbance as a rocking cradle.” Ormsby added that, “White pants and kid gloves had better be discarded.”

Other stagecoach routes took a more direct route west from Saint Louis to San Francisco passing directly through the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains across Wyoming. In 1870 Mark Twain made the trip by stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to Virginia City, Nevada, site of the famous Comstock gold lode, where he worked for a newspaper. Twain kept an account of his travels by stagecoach across the West and published a detailed and interesting account of the trip titled Roughing It.

Twain’s description of a stagecoach station in the middle of the prairie is particularly interesting as it shows the adaptions and meager life style in the vast grasslands with no timber for building.

The station buildings were long, low huts made of sundried, mud-colored

bricks, laid up without mortar. The roofs, which had no slant to them worth

speaking of, were thatched and then sodded or covered with a thick layer

of earth, and from this sprung a pretty rank growth of weeds and grass.

It was the first time we had ever seen a man ’s front yard on top of his

house. The buildings consisted of barns with stables for twelve or fifteen

horses, and a hut used for an eating-room for passengers.

Twain wrote that the station’s window was a square hole with no glass and the floor was hard-packed earth. By the door outside was a tin wash basin, a pail of water and a piece of yellow soap, but no towel. A mirror hung in one corner with half a comb hanging by a string. The few three-legged stools provided seats at the table, which was a greasy board on stilts. A battered tin plate, a knife and fork and a tin pint cup were at each man’s place. Twain wrote, “We could not eat the bread nor drink the the “slumgullion.” (Slumgullion is a thin stew with little substance.)

Because the stagecoach stopped only for eating and changing horses, all passengers managed to catch what sleep they could while bouncing along in the coach. Mark Twain gave a vivid account of traveling through the night without stop.

We never moved a muscle all night, but waked at early dawn in

the original positions, and got up at once, thoroughly refreshed, free of soreness and brim full of friskiness. After breakfast we bathed in

Horse Creek [Wyoming]—an appreciated luxury, for it was seldom

that our furious coach halted long enough for an indulgence of

that kind. We changed horses ten or twelve times in every

twenty-four hours—rather changed mules—and did it every

time in four minutes. It was lively work. As our coach rattled up to

each station six harnessed mules stepped gayly from the stable;

and in the twinkling of an eye, almost, the old team was out and the new one in and off and away again.

After getting accustomed to the bouncing ride of the stagecoach, Twain wrote, “Our coach was a great swinging and swaying stage of the most sumptuous description—an imposing cradle on wheels.”

Although the mail and passenger service by stagecoach lasted only a short time the stagecoach routes played a major role in connecting the east and west of the continent before the railroad and hold a prominent place in the history of the West.

Sources

Ahnert, Gerald T. Butterfield Overland Mail Company stagecoaches and stage (celerity) wagons used on the southern trail. Syracuse, New York: Gerald Ahnert. 2013.

Ely, Glen Sample. The Texas frontier and the Butterfield Overland Mail. 1858-1861. Norman: Oklahoma University Press. 2016.

Helmich, Mary, A. Stage styles: Not all were coaches. California Department of

Parks and Recreation. 2008. Retrieved from https://www.parks.ca.gov/? page_id=25449.

Twain, Mark. Roughing It. Hartford Connecticut: American Publishing Company. 1873. (Many newer editions are available.)

The first mention of a coach was in an English manuscript from the thirteenth century. The first known stagecoach route in Britain began much later, in 1610, and made a short run from Edinburgh to Leith, Scotland a distance of only three miles. This small beginning was soon followed by a proliferation of other routes, and by the mid-seventeenth century, a basic stagecoach infrastructure was in place in Great Britain. With infrastructure in place the stagecoach then became the primary means of carrying mail and passengers between cities. In 1649 Edward Chamberlayne wrote admiringly about this new transportation in England.

“Besides the excellent arrangement of conveying men and letters on horseback, there is of late such an admirable commodiousness, both

for men and women, to travel from London to the principal towns in

the country, that the like hath not been known in the world, and that

is by stage-coaches, wherein any one may be transported to any

place, sheltered from foul weather and foul ways; free from

endamaging of one's health and one's body by the hard jogging

or over-violent motion; and this not only at a low price (about a shilling*

for every five miles), but with such velocity and speed in one hour, as

that the posts in some foreign countries make in a day.”

(*NOTE: One shilling in 1650 was equivalent to $8.25 in today’s dollar. Today a shuttle from my house to the Tucson airport costs $49 or about $10 for every five miles. Coincidentally, that shuttle is called Stagecoach Express.)

In support of this growth in stage lines, coaching inns developed as stopping points for travelers on longer routes as between London and Liverpool. These inns became stopping points or stages in the journey that provided food and drink for the passengers and a change of horses. The business of running stagecoaches or the act of journeying in them was known as staging—hence the name stagecoach.

During the American colonial period, the stagecoach was the primary carrier among the New England colonies. In the early nineteenth century railroads began to be built in the United States and by 1845 were built as far west as Saint Louis, but there was still no way to send mail to San Francisco except by a long voyage by ship around South America.

In 1850 a ship from New York took about 200 days (6.5 months) to sail to San Francisco. The discovery of gold in California led to a rapid increase in population in the west and created a strong need for a shorter communication time with the west coast. To this purpose the United States Congress authorized a contract in 1857 for overland mail service from Missouri to California via horse-drawn conveyances. This far-reaching contract was awarded to New York businessman John Butterfield.

The visionary John Butterfield developed a grand scheme for a stagecoach route to carry mail and passengers from the railhead in Saint Louis to San Francisco in only twenty-five days. It took a year to work out the details, and Butterfield decided on a southern route, south from Saint Louis via Arizona to avoid bad weather. In addition, he refused to carry gold or silver in an effort to cut down on attacks by highwaymen. Butterfield built 139 relay stations along the 2,795-mile route, about twenty miles apart with meals and horses at each of the stops. For the twenty-five-day trip, the Butterfield stages did not stop for the passengers to sleep. Their only choice was to sleep on the moving stage.

In New Mexico and Arizona the Butterfield trail passed through Apache territory, and for two years the Chiricahua Apaches permitted safe passage by an agreement under which the tribe would be compensated and also provide firewood for the stage stations. This arrangement came to an end when an army lieutenant had an angry exchange of words with the Apache chief, Cochise, and the lieutenant put Cochise in jail. This unfortunate event led to hostilities between Apaches and Arizona settlers for the next twenty-five years.

In 1860 the Pony Express, a single rider on horseback, began carrying mail over a central route and shortened mail delivery time even further. The following year, the Butterfield Overland Mail route was discontinued and the Pony Express joined forces with Wells Fargo, which began in 1852 as an express and banking service.

Stagecoaches became such a fixture for travel that it is worth looking at them in some detail. Among several variations and sizes of stagecoach, two stand out as most used in the western United States. One was the Concord Coach, originally built in Concord, New Hampshire. This coach could hold six passengers inside with a few more sitting on top. Usually four horses were sufficient, but often six were used. The inside of the Concord style coach measured four feet wide and about four and one-half feet high. The seats were boards with padded leather upholstery, which were said to be harder than a bare board. The walls had cloth coverings.

A second type of stagecoach, built in Concord and Albany, was the celerity (swift) wagon. This lighter-weight wagon was designed by John Butterfield for use on his mail route. To decrease weight, the celerity wagon had canvas instead of a wooden top and larger window openings with canvas roll-down curtains. The larger windows reduced weight but gave less protection from constant dust. For extra stability the wheels were farther apart with longer axles. Wider steel rims on the wheels served well for traveling on sandy roads. Some stagecoaches had seat backs that let down to create a flat bed so passengers could sleep. However this feature was of limited use if the coach was full of people. Luggage was stored in a compartment on the back as the canvas roof could not bear weight.

One Butterfield passenger, a Mr. Ormsby, wrote in 1858 about his efforts to get some sleep while bouncing along in a celerity wagon. “Perhaps the jolting will be disagreeable at first, but a few nights without sleeping will obviate that difficulty, and soon the jolting will be as little disturbance as a rocking cradle.” Ormsby added that, “White pants and kid gloves had better be discarded.”

Other stagecoach routes took a more direct route west from Saint Louis to San Francisco passing directly through the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains across Wyoming. In 1870 Mark Twain made the trip by stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to Virginia City, Nevada, site of the famous Comstock gold lode, where he worked for a newspaper. Twain kept an account of his travels by stagecoach across the West and published a detailed and interesting account of the trip titled Roughing It.

Twain’s description of a stagecoach station in the middle of the prairie is particularly interesting as it shows the adaptions and meager life style in the vast grasslands with no timber for building.

The station buildings were long, low huts made of sundried, mud-colored

bricks, laid up without mortar. The roofs, which had no slant to them worth

speaking of, were thatched and then sodded or covered with a thick layer

of earth, and from this sprung a pretty rank growth of weeds and grass.

It was the first time we had ever seen a man ’s front yard on top of his

house. The buildings consisted of barns with stables for twelve or fifteen

horses, and a hut used for an eating-room for passengers.

Twain wrote that the station’s window was a square hole with no glass and the floor was hard-packed earth. By the door outside was a tin wash basin, a pail of water and a piece of yellow soap, but no towel. A mirror hung in one corner with half a comb hanging by a string. The few three-legged stools provided seats at the table, which was a greasy board on stilts. A battered tin plate, a knife and fork and a tin pint cup were at each man’s place. Twain wrote, “We could not eat the bread nor drink the the “slumgullion.” (Slumgullion is a thin stew with little substance.)

Because the stagecoach stopped only for eating and changing horses, all passengers managed to catch what sleep they could while bouncing along in the coach. Mark Twain gave a vivid account of traveling through the night without stop.

We never moved a muscle all night, but waked at early dawn in

the original positions, and got up at once, thoroughly refreshed, free of soreness and brim full of friskiness. After breakfast we bathed in

Horse Creek [Wyoming]—an appreciated luxury, for it was seldom

that our furious coach halted long enough for an indulgence of

that kind. We changed horses ten or twelve times in every

twenty-four hours—rather changed mules—and did it every

time in four minutes. It was lively work. As our coach rattled up to

each station six harnessed mules stepped gayly from the stable;

and in the twinkling of an eye, almost, the old team was out and the new one in and off and away again.

After getting accustomed to the bouncing ride of the stagecoach, Twain wrote, “Our coach was a great swinging and swaying stage of the most sumptuous description—an imposing cradle on wheels.”

Although the mail and passenger service by stagecoach lasted only a short time the stagecoach routes played a major role in connecting the east and west of the continent before the railroad and hold a prominent place in the history of the West.

Sources

Ahnert, Gerald T. Butterfield Overland Mail Company stagecoaches and stage (celerity) wagons used on the southern trail. Syracuse, New York: Gerald Ahnert. 2013.

Ely, Glen Sample. The Texas frontier and the Butterfield Overland Mail. 1858-1861. Norman: Oklahoma University Press. 2016.

Helmich, Mary, A. Stage styles: Not all were coaches. California Department of

Parks and Recreation. 2008. Retrieved from https://www.parks.ca.gov/? page_id=25449.

Twain, Mark. Roughing It. Hartford Connecticut: American Publishing Company. 1873. (Many newer editions are available.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed