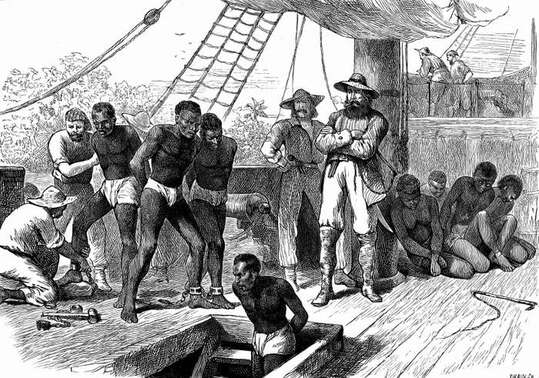

African captives being loaded and shackled on a slave ship. Anti-slavery Internationa

African captives being loaded and shackled on a slave ship. Anti-slavery Internationa Old trading routes carried many commodities as discussed in the blog on “The Silk Road.” Usually we think of these commodities as high value goods, such as silk and spices, with sufficient profit to pay for the long journeys. It was also common for one of the commodities to be humans, and by the early seventeenth century (1619) humans were transported as captured slaves from West Africa across the Atlantic Ocean to North America and South America.

Slavery has existed in many cultures dating back before recorded history. The practice of owning another human began with the emergence of the stratified societies of civilization, probably about 11,000 years ago. Slavery appears very rarely in hunter-gatherer societies having little or no social stratification.

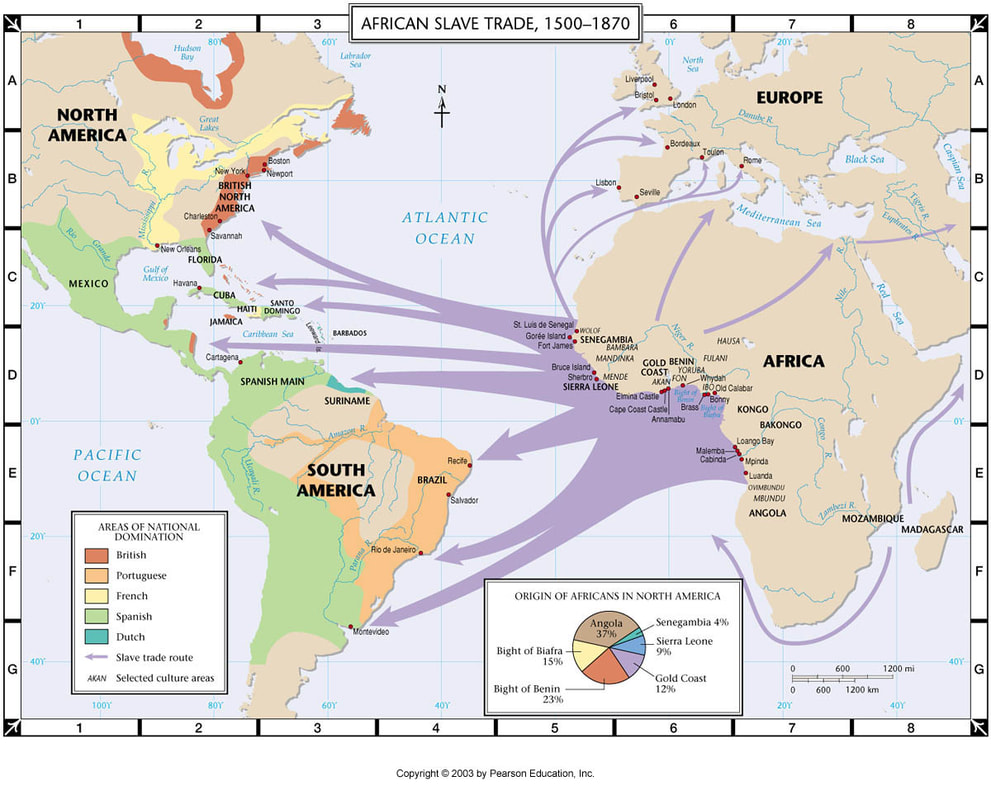

Captains of seventeenth-century slave ships acquired African slaves at various points on the African coast from Arab and West African traders. In the beginning traders brought slaves to Spain, Portugal, the island of Madeira, and the Canary Islands. When Europeans settled the Americas they built large plantations of labor intensive crops such as sugar cane, cotton, and tobacco, and this in turn created a greater need for captive slaves from Africa in the New World.

Slaves were usually captured through tribal warfare and sold to African slave dealers on the coasts, who acted as middlemen selling slaves to the European ship owners. African coastal societies benefitted from a steady supply of European textiles, ironware, and firearms—all in exchange for African captives. The firearms led to more forced capture resulting in more slaves sold to the dealers on the coast. This arrangement made it possible for ship owners to have a steady supply of slaves sufficient to fill their lower decks. From this it is clear that the Africans were considered nothing more than cargo for the next ships. As New World settlement expanded, Brazil, several Caribbean countries, American southern states, and African kingdoms all prospered in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries because of the slave trade. Their economies relied heavily on slave labor.

Warfare and kidnapping clearly had a damaging effect on the populations that were victimized by the slave trade. Many African communities tried to defend themselves from slave raiders. Others retreated to more remote and defensible geographical regions to escape attacks and capture. This upheaval dispersed or destroyed many native African communities forever.

Nearly one-third of all transatlantic slave voyages originated in British ports. They sailed from England to Africa with merchandise, then transported ship loads of Africans to Caribbean islands before ruling the trade illegal in 1807. During that period slave trading became essential to the well-being of the British empire. Among other countries transporting slaves across the Atlantic, Portugal ranked nearly as high as Britain, followed closely by France. Some American ships also carried slaves.

The Atlantic voyage from West Africa to the New World was the middle segment of a three-part voyage with a different cargo on each part. First, ships left a European port with various manufactured goods such as cloth, whiskey, and metal utensils like pots, pans, and knives. These goods were taken to West Africa and traded for slaves, then taken to destinations in South America, the Caribbean, and North America. In those ports the ships would load sugar, tobacco, cotton, and rum, and begin the third leg of their trading voyage back to Europe. Much of the success of the these three-part voyages required an astute captain with the savvy to handle business deals, make sure the slaves survived, and return a handsome profit for the financiers back home.

If the Atlantic served as the slave trade’s central artery, the networks of roads, paths, and waterways in the Americas that transported enslaved people from ports to plantations, mines, and cities were the capillaries—much the same as the slave routes on the African interior had brought them to the coastal port cities.

Each slaving voyage outfitted in London, Bristol, or Liverpool required a network of financial connections. British ships were usually financed by a group of investors in London. Manufactured goods bought on credit were loaded onto ships bound for West Africa. Because the entire venture was based on credit there were huge time lags before the manufacturers making the goods received payment from the financiers. Slave ships were away from their home port for a year or more. New World planters sending their harvests to London also had to wait long periods for payment for their produce. Financially the system was a success, but the human side of it was a disaster which the British outlawed in 1807.

British merchants and the captains of the slave ships developed their own contacts in Africa and in the Americas. Ship captains soon learned what manufactured goods were preferred by particular African traders and found which planter agents in each New World port could be relied on for the best deal on cotton, sugar or tobacco. Investors relied wholly on slave-ship captains to care for their investment in expensive ships and cargos and who were expected to have the experience needed to provide profits for the enterprise. A successful captain was paid handsomely in wages and bonuses at the end of a successful trip.

By the time the British abolished slave trade, their slave ships alone had completed voyages carrying more than 3.2 million Africans on the middle voyage from Africa to the New World. First the British ended the Atlantic slave trade, and the next year the United States also stopped importing slaves. After America ended importation of slaves plantation owners were able to rely on the natural increase among slaves. Slavery in the United States officially ended in 1862 with the Emancipation Proclamation, but not until June 19th, 1865 (Juneteenth) did all locations actually stop the practice. In the 1850’s Britain attempted to stop the Atlantic traffic of slaves to Brazil, but the importation continued until 1888 when Brazil became the last country in the New World to outlaw slavery.

The Atlantic crossing of a European slave ship constituted a traumatic experience for the millions of Africans. The slave ship was in effect a floating dungeon. Before the Atlantic crossing even began, some slaves suffered months of confinement as the ship lingered on the African coast while the captain waited for enough captives to make the voyage profitable. Africans who made the journey had to survive disease, malnutrition, crowded space, not to mention the trauma of of being uprooted, whipped, and confined in a ship.

Although the British and Portuguese dominated the Atlantic slave trade, the the third-ranking French also shipped about one million Africans to Haiti in the late eighteenth century.

Of the 12.5 million Africans loaded onto 35,000 Atlantic ships by American and European slave traders, there are a few firsthand accounts of the slaves’ experience. One such account was published in 1789 by an African-born man living in London, titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavas Vassa, the African. Written by Himself, (London, 1789). The author, Olaudah Equiano, detailed his life journey from African captivity, the Atlantic crossing, life in slavery, and eventual freedom. Equiano’s book presented a body of evidence that supported the cause against transatlantic slaving by Britain.

In his biographical book, Equiano vividly described the experience of fear and confusion in the Africans as he at the age of eleven, and his sister, were captured, walked for several months from trader to trader until they finally reached the coast where they were loaded onto ships. He described in detail the role of the white traders and the African chiefs in capturing and selling slaves.

The role of the African chief was to capture neighboring tribes through warfare in which he put himself at risk of capture. Equiano wrote, “…if he prevails and takes prisoners, he gratifies his avarice by selling them, but if his party be vanquished, and he falls into the hands of the enemy, he is put to death.” After some bargaining the chief “…accepts the price of his fellow creatures’ liberty with as little reluctance as the merchant.”

Equiano had never seen white people, sailing ships, nor even imagined anything comparable to the stinking holds of a slave ship. Equiano wrote that he and all the other Africans were “in another world,” and indeed they were. Equiano later described his first experience on the ship.

“I was soon put down under the decks, and here I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. “…the air soon became unfit for respiration from a variety of loathsome smells and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died.”

Slave ships became known for the stench they emitted. Some sailors claimed they could tell a distant ship was a slaver by the downwind smell. Unfortunately many slaves did not survive. The main causes of death among slaves at sea was malnutrition, and disease due to the dreadful sanitation conditions below decks.

Equiano’s life from that point took a far different course from most slaves who were sold to plantation owners. In 1754, he was purchased by Lieutenant Pascal, an officer in the Royal Navy. Pascal sent Equiano to London for schooling, then later sold him to a ship captain where he learned sailing. The captain eventually sold Equiano to an American planter named Robert King. Equiano’s rudimentary education provided him with some basic skills and prompted King to put him to work in marketing rather than in the fields.

After three years Robert King allowed Equiano to purchase his own freedom. As a free man, Equiano found employment using his sailing experience to earn a living in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. Obviously Equiano’s experience was far different from the much harsher life of most slaves brought to the New World.

American slaves working on plantations experienced varied treatment by their owners. Some were sold away from their own families to other regions, some were beaten or forced into sexual relationships with owners, while some were treated fairly and even given rudimentary education. Many recent publications recount these experiences.

Over more than 300 years the Atlantic trade routes carried 12.5 million African men, women, and children to the New World. Approximately 1.5 million (12 %) did not survive the dreaded middle passage voyage.

Sources

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: Written by Himself. Hollywood, FL: Simon and Brown. 2018.

Wikipedia. History of slavery. Retrieved from: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_slavery

Hazard, Anthony. The Atlantic slave trade: What too few textbooks told you- Retrieved from: ed.ted.com

Mustakeem, Sowande M. Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 2016.

UNESCO. Transatlantic Slave Trade: Middle Passage. Retrieved from: slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/index.cfm?id=A0032.

UNESCO. Transatlantic Slave Trade. Slave Trade Routes: British Slave Trade. Retrieved from: slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0096.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed